The worst scene in MachineGames’s Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus can most charitably be described as a political cartoon, but that is lending it more credit than it deserves. In a game full of odd physical gags haphazardly stuffed wherever they’ll (kind of) fit, player character William “BJ” Blazkowicz’s unexpected meeting with Hitler is the most egregious and inexplicable of them all. But most troublingly, it is used to abruptly put an end to serious questions the game previously raised.

For a while, Wolfenstein II invests itself in humanizing Nazis. It does this not with the goal of creating empathy but to acknowledge the reality that Nazis are not distant monsters; they’re people who live among us who have chosen to do and believe monstrous things. When Blazkowicz meets Sister Grace, the leader of the Black Liberation Front—a fictionalized version of the Black Panthers—she describes for him the horror of returning to the surface after Germany dropped a nuclear bomb on New York City. Blazkowicz says, “Monsters did this.” Sister Grace, without hesitation, dismisses him: “Not monsters. Men.”

There is a clear divide between Blazkowicz and Sister Grace’s visions of America. Sister Grace watched the Nazi takeover of the United States in real time, and saw what Blazkowicz didn’t—just how much of America, the white America that Blazkowicz grew up in, is happy and comfortable under Nazi leadership. More importantly, she knows from her lived experience that this oppression was already a part of the fabric of America. Even though Blazkowicz grew up with an abusive, racist father, he is stubbornly ignorant of that hate being widespread and systemic. No matter what evidence Sister Grace offers up, Blazkowicz insists that America only needs to be freed from the Nazis.

Although Blazkowicz convinces the Black Liberation Front that a revolution is still possible, his time on the ground in America is a fight between these two visions. When Blazkowicz goes to Texas to infiltrate the Oberkommando, he is confronted by the America Sister Grace already knew. Klan members walk the streets ostensibly without shame (although still hooded), and Blazkowicz witnesses a pair of them attempting to ingratiate themselves to a Nazi soldier. Minutes later he sees a mother encouraging her child to learn German, then nervously hurrying him out when a Nazi soldier enters the building. Be it for fear or reward, America has chosen to roll out the red carpet and welcome Nazis as their leaders and as a part of their cultural identity. When Blazkowicz confronts his father in his childhood home, it seems that all of this should be coming to a head. His father has gone from racist abuser behind closed doors to proud Nazi collaborator. Blazkowicz isn’t surprised to discover that his father gave his Jewish mother up to the Nazis; his father has remained the same person. Only the conditions around him have changed. Despite all of this, Blazkowicz resists having to kill his father, only attacking when it is clear that there is no other option. This should be the point where Blazkowicz realizes that the Nazis were able to take over so quickly because there were enough men like his father to help them. This should be the point where he realizes that these people were present in America before the Nazis came, and that they will remain after. But in the name of action the game barrels forward, and Blazkowicz never seems to internalize this connection.

After being captured, executed, and secretly brought back to life, Blazkowicz travels to New Orleans to rescue a group of freedom fighters. His drunken argument with their leader, Horton Boone, finds Blazkowicz again opposite a potential ally. Boone does not hesitate to call him out as a tool of the American war machine, and Blazkowicz is equally eager to dismiss Boone on the basis of his supposed communist sympathies. For people like Boone and Sister Grace, the fight for justice and equality is not with the state, but against it. Blazkowicz, who was given a place and a purpose in the military, sees this fight as inextricably linked to America, and even sees America as a force representing these ideals. When Blazkowicz points out that despite all their ideological differences, in the end they’re still both fighting Nazis, it’s only half true. For Blazkowicz, Nazis are the enemy. For Boone and Grace, the Nazis are one of many standing between them and equality.

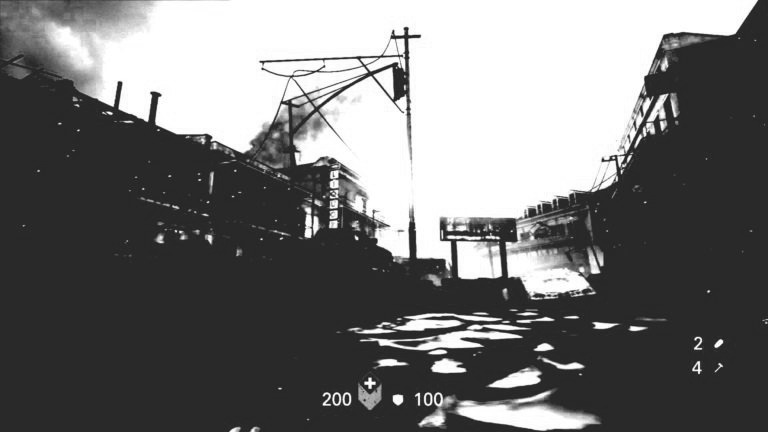

The moment Hitler enters the game, all tension between these ideals ends. Blazkowicz meets Hitler after disguising himself as an actor to audition for the role of … himself … in a Nazi propaganda film. Every bit of the scene is absurd, from its setting on Venus, to the Ronald Reagan cameo chattering in the corner. It is clear that the time for somber contemplation is gone. Hitler bursts into the room, markedly wretched from first glance, hobbling around in his bathrobe. His paranoia and anti-semitism is played for laughs as he shoots an actor in the face for calling him “Mr. Hitler.” The director of the film, Helene, forces a grin and with an exaggerated gesture crosses the newly deceased off of her audition list. Hitler’s degenerated physical state is similarly used for gags. He urinates in a bucket and subsequently on the floor in full view, and goes into a coughing fit so severe that he ends up vomiting. The puke puddle is then used as a comedic prop throughout the rest of the scene, most notably with Helene accidentally stomping her foot into it and then wiping her shoe on the carpet with sheepish disgust. After Hitler hurls, he clings to Helene, feebly calling out for his mother, recalling Blazkowicz’s prayer-like monologues to his own dead mother. But here, it is just another approach for ridicule.

All of this is not to say that it is wrong, or in poor taste to ridicule Hitler—it can be cathartic, or empowering, and it might also annoy Nazis which is always a bonus. However, Wolfenstein II uses this caricature of Hitler as a tool to beat back the question of who and why the resistance are really fighting. Hitler’s image resembles World War II era anti-Nazi propaganda, rabid yet weak, with dark bags under his wild, sunken eyes. The absurdity of the entire scene feels almost propaganda-like in itself, as if it is being acted as poorly as the line reading for the film. Seeing Hitler in this state seems to awaken the young patriotic soldier within Blazkowicz. After so many challenges to his faith in America, and in himself, coming face to face with the enemy reminds Blazkowicz that he went into this war to do one thing: kill Nazis. The game commits thereon to treating Nazis not as monstrous humans, but as monsters, leaving the potential of its commentary behind. It even positions Blazkowicz standing over Hitler, able to crush his head with a stomp, like a robot does to his friend Caroline’s decapitated head earlier in the game. His frailty is built to be revelled in, as the Nazis revelled in yours.

Killing Nazis may be enough for Blazkowicz, but it leaves the depth of the problem behind, along with conveniently forgetting the larger battles being fought by Sister Grace and Horton Boone. Although Wolfenstein II has drawn much praise for its brief foray into politics, the truly political questions are never voiced. What will be done about the American citizens, like Blazkowicz’s father, who actively participated in genocide? What systems were already in place in America that allowed the Nazis to carry out their agenda so quickly? If the Nazis are defeated, what will America look like? If the Nazis are defeated, has the battle actually been won?

Falling into the tropes of propaganda, MachineGames uses Hitler like a hammer that flattens down any necessary wrinkles in Wolfenstein II’s narrative. It uncomplicates and simplifies the image of the enemy. After continually showing Blazkowicz’s ideals as separate from those of the other resistance members, the appearance of Hitler reminds Blazkowicz, and vicariously the player, of what they are really (supposedly) fighting. It returns the story firmly to safe, good old fashioned Nazi killing. However, this simplicity is at odds with the world MachineGames has shown. The fights for racial and economic equality that Sister Grace and Horton Boone represent are left behind like forgotten set dressing as Blazkowicz and his ragtag gang rocket from raunchy spectacle to bloody spectacle, carrying the game further and further from its redeeming qualities. Gruesomely killing Frau Engel ends the personal quest for revenge Blazkowicz carried with him throughout Wolfenstein II, but in the course of the larger fight, her death is mostly symbolic. As Blazkowicz’s comrades shout about freedom, he proposes to his partner; it is clear that for him, this was personal. Although the game and the characters refuse to acknowledge it, they are still fighting separate wars.

Alex Dalbey is a writer and zinester currently working out of St. Paul, Minnesota. They write about LGBTQ issues, videogames, comics, and sex. Follow them on Twitter.

,