People love Blood’s third level, “Phantom Express.” Seeing train tracks whip by like that in a ‘90s shooter was a tasty trick, but what stands out more is probably the dining car. You are handed a 60 second dual wield power up. The game so far has boxed you into rooms with three or so foes and few shotgun shells between them. Behind twin doors is a full social: Two bars facing each other. A dozen armed men in cloaks drowning their eldritch troubles in non-enchanted glasses of rye. You plop in. Blazing. Bouncing around the room like a pogo Neo. Mowing down as many cultists in one chamber as you’ve killed in the entire game. Bits of glass pop like confetti. Blood pisses out of their wounds like a cardiovascular sprinkler system. Their bodies fall into red pools with the sound of wet towels. (The first time I played this I cleared the room only to walk through the back door, slip off the end of the train and die. It happened the second time too. And the third. God, what a badass.)

The ‘90s introduced the food pyramid, suggesting kids eat more corn and spaghetti or whatever. Likewise acceptable norms for violence in the nine year old’s diet were getting cranked. Not just the Hellraisers and Evil Deads secretly peeped at sleepovers, but the sinew connecting children’s entertainment to “adult stuff.” A fiercely competitive sector recognizing a target demographic satisfying themselves elsewhere. It ranges from family horror like Are You Afraid of the Dark? to Spawn Pogs, the bottle cap child fad gauging that a comic book about hell’s chief of staff goring a child-killing ice cream truck driver is ‘close enough’ to share a shelf with The Lion King.

An aspiring grade four Todd McFarlane, I was competing too.

I drew a picture of a mutant with a mace for an arm (named “Mace”) standing over the body of a Rancor-like troll. I was about to show this drawing to a friend (let’s call him Ivan) when I decided the doodle could be spicier. I took out a pencil and red crayon. I gave the troll’s body five rice-shaped pocks, filling them in with the meanest Crayola had to offer. I showed Ivan the drawing. Didn’t get much of a reaction.

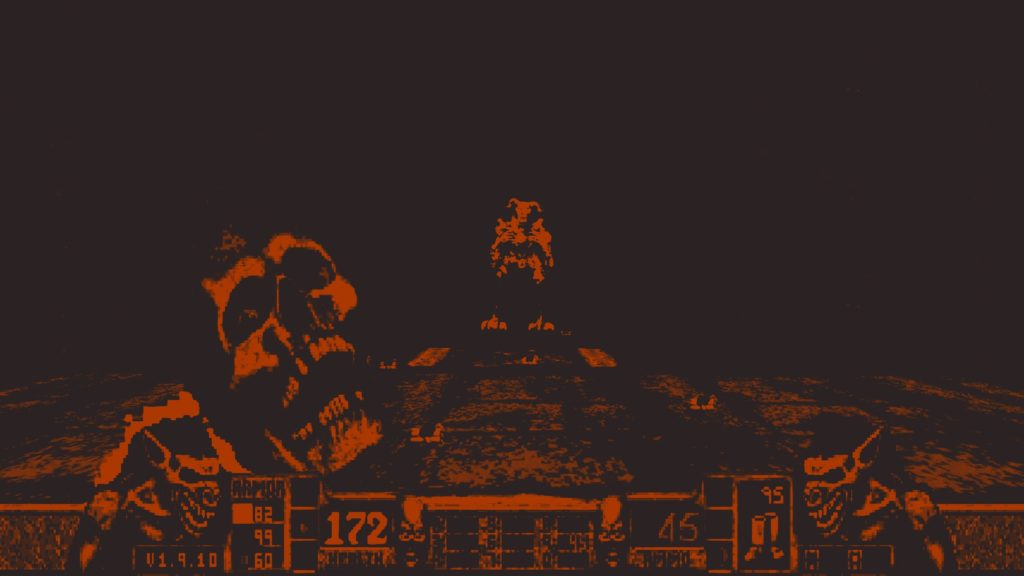

‘90s shock—the kind I was trying to replicate with crayons—feels precious. Provacateuring is so much more vicious and personal in 2019 compared to Tom Savini gore and farts loud enough for someone to call them “rude.” When ‘80’s camp blended with ‘90’s brutality, you got a loud screaming bug-eyed skull. You want the best screaming bug-eyed skull? It’s unmistakable. It’s Blood-lust. You want to play the videogame Blood.

Videogames were the richest source of this pathetic adolescent violence. DOOM. Duke Nukem. Alien vs. Predator. For kids looking for a headrush, 2.5D shooters were like diving into a McDuck vault full of low-rez offal. By no coincidence I played Wolfenstein 3D for the first time at Ivan’s house. He mowed down SS goons and their hounds while I fiddled with a Wooly Willy, the toy’s magnetic shavings spilling out and staining my hand, a pouring of guts horrifying me more than the killing spree two feet ahead of me.

DOOM and Wolfenstein are classics. Influential, inarguable, and shredded. Blood is something else. It’s the finest aged cheese. An armour-like rind filled with divine goos. Authentic stink. The best 2.5D games have to offer and so pure in ‘90s schlock it feels clairvoyant. It is the core of this pastiche. Children parallel to global violence committed by their elders, mistaking violence itself is a sign of sophistication. Adults more or less believing the same.

In Blood you are Caleb. Caleb dresses like a scarecrow and swings around a pitchfork. Caleb serves the Serbian demon Tchernobog (same as the one in Disney’s Fantasia) until Tchernobog betrays his inner circle, slaughters them all. Rising from his grave, Caleb wants to kill Tchernobog, all his cultists, his ghouls, his giant spiders, his three-headed dog, his shark-men, and bury his friends better than he was buried himself.

Blood might be stupid, but it is a fantastic videogame. Most shooters at the time had one-gun-suits all attitudes, new weapons causing only more powerful splash damage. Blood’s guns fit like a glove to enemies. Nuisances like hell hounds and gargoyles can be quickly subdued with some zaps from the Tesla Cannon. Cultists, the default enemies who scramble in circles and scream incoherent Latin, are best dealt with a flare, which immolates them within a few seconds. Magic weapons like the voodoo doll can make quick deaths, but drain your health if you aren’t aiming properly.

The maps are astounding. Caleb’s revenge tour spans the world. Carnivals. Arctic shipwrecks. Active warzones. A civilization carved out of tombstones. It’s the extended universe of amusement park haunted houses. Everything feels like someone else’s gallow. Everyone’s a monster or being murdered. Throughout the world you encounter these poor chumps, shirtless men in torn jeans who flee screaming from murderers, demons, falling bombs, what have you. The sadists among us can kill them without consequence. I prefer to let them live. Wait till they stop panicking. See where they go. Watch them park themselves in a corner or facing a wall. There’s nowhere to run. They live in a slasher film and they know that. If they aren’t mauled today, they’ll be used in tomorrow’s sacrifice. That existence seems much crueler than death.

Blood is the dream you have the morning after an all-night horror bender. The game is filled with nods that border on infringement. Freddy’s glove hangs on the wall of the boiler room level. Jack Torrence’s frozen body sits in a snowy hedge maze. The possessed hands from Evil Dead II are a recurring enemy. My favorite level is deadass called Crystal Lake. It’s one of the biggest maps, with elaborate tunnels and shortcuts, wooded passages, and wide swamp-like bodies of water. At several points Jason’s signature “ch ch ch” whispers, but on the off-chance you run into Vorhees you’d probably accomplish more damage than Creighton Duke.

These references were the doing of lead artist Kevin Kilstorm. Kilstorm came in mid-production and filled in for fantasy artist Christopher Rush, who left to work on a new card game called Magic: The Gathering. Rush’s vision for Blood was a more serious, Lovecraft affair. Kilstorm was the team’s Matthew Lillard (Scream or Serial Mom, take your pick). A living Fangoria subscription, whose infectious enthusiasm for cassette horror and homemade Freddy Krueger models made the game more camp and ultimately more likeable. Kevin Kilstorm was the guy every ‘90s kid wanted to be, made the game every ‘90s kid wanted to play, was the funhouse mirror for adolescents to look at and imagine what they might look like as adults. I don’t think adults are much more mature than their juvenile years. You look back at a lot of studio Stallone blockbusters and wonder if they were being made for kids or by kids. Hard to say. The only movies that come out now are about superheroes, clowns, or both.

At some point (9/11?) every shock jock of the 1990s decided they had some kind of moral imperative. Howard Stern went from subterranean pervert to primetime fixture. Sweatshirt comedians like Jon Stewart, Bill Maher, and Joe Rogan somehow became North America’s choice moderators. South Park became as preachy as Davey and Goliath. I’d bring up Eminem but he got moody by the third single. All the big kids got these delusions of grandeur, recognizing the responsibility of popularity, but perhaps misjudging just how much should be shouldered by the world’s flatulists. Now every new shock jock skips to the part where they imagine themselves as a philosopher and it’s a neverending nightmare.

Video games, the medium born into shock, changed too. It’s violence became less camp and even its gestures of destruction took on bleaker tones. 2001’s Twisted Metal: Black was still a clown-starring demolition derby but it opens on the Rolling Stone’s depression anthem “Paint It Black” for some reason. Rockstar, whose Grand Theft Auto games were a way for CD ROM teens to wreak havoc on model towns, pivoted themselves towards loose social satire. Add on top the Red Dead games, which play identically but have the veneer of a noble stallion even if its own horses constantly trip over wagon wheels and kick you in the head. Nothing illustrates Rockstar’s vision of growing up like realistically contracting horse scrotums. By the time these trends were kicking up, Kilstorm was working on No One Lives Forever and Alien vs Predator 2.

Blood won’t suffer time. It was—and still somehow is—the big kid. It’s the cool cousin. It’s the story of the haunted hayride that sounds too good, too real, to be true. It has no shame or misgivings about its shock value, its irreverence. A game that knows about its eventual preciousness. Perhaps the most telling detail are how many rooms have light switches, in case the darkness gets too scary for the kiddies.

Zack Kotzer is a former carny and current writer. His work has appeared in Vice, The Globe and Mail, The Atlantic, and Toronto Life. He has an upcoming book about pinball, his favorite thing in the whole wide world. He’s on Twitter.

,