Spoilers for all of Disco Elysium below.

In Disco Elysium, lieutenant Kim Katsuragi is both your partner and your guide. Elysium’s protagonist, Harry Du Bois, is a ruinously drunk detective whose latest binge has obliterated his memory; he leans on Kim, a steady 20-year veteran of the force, to explain the game’s central murder case and the world to him.

Before the player even learns their own name, they learn to rely on Kim’s judgment—he immediately outlines a plan, establishes that Harry’s badge is missing, and begins the work of interviewing suspects. It takes a while to see that Kim, the voice of reason, is usually wrong.

Kim tells you that:

- It’s a waste of time to figure out what’s behind a locked door next to the scene of a murder.

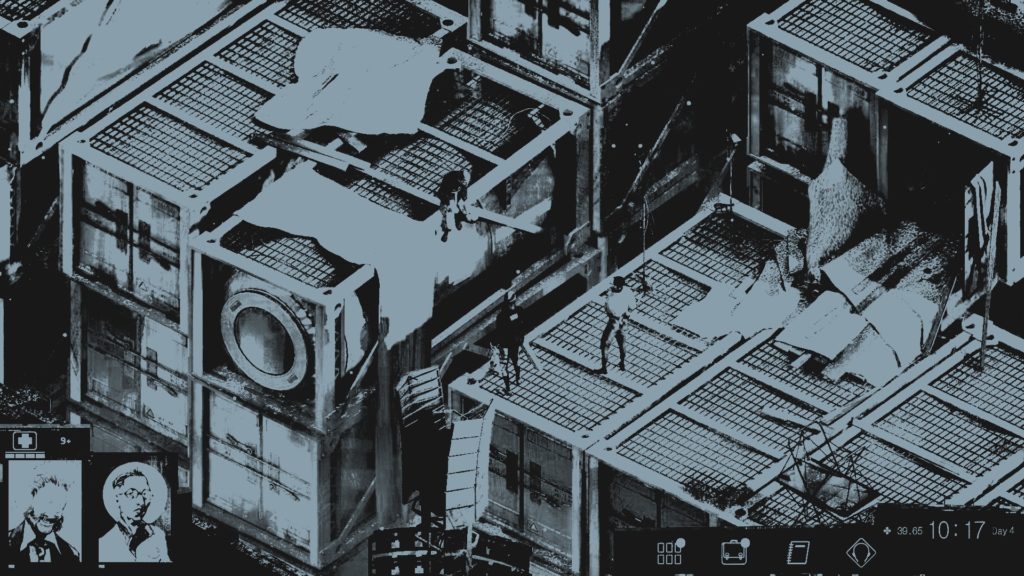

- There won’t be anything interesting inside the conspicuous shipping container in the harbor.

- There’s no good reason to collect a set of T-500 battle armor.

- There’s no mystery behind the bankruptcies of businesses in the Doomed Commercial Area.

- The case will not have a sexy or supra-natural twist.

- There are no “sequence killers” at work in Martinaise.

- Cryptids do not exist.

Kim’s advice comes from a saner world than the one Harry has really woken up in. The sober lieutenant sets up most of the twists and “miracles” that later shape the plot by telling Harry that they could never happen. (Some of Harry’s first wild guesses about the murder, which pass as jokes, are dead-on.) He exerts a skeptical gravity that the story gradually escapes.

It’s not procedure that cracks the case, but Harry’s intuitive and “supra-natural” methods—talking to the victim’s corpse to learn there’s a bullet in its mouth, talking to the wind to learn which building the suspect is hiding beneath. But the conflict between Harry and Kim is more than the immutable math of buddy cop stories, where one must be crazy and the other too-sane, one fat and the other skinny, one Mulder and the other Scully. Kim also sets up the game’s essential mystery, which is not “who killed the hanged man” but “what kind of story is this?”

For almost its entire running time, Disco Elysium plays as comedy. Its humor is absurd, dramatic rather than dry, often internet-y (probably the only game where that’s a compliment) in its hostility toward affectation; it revels in the protagonist’s humiliation, somehow without inflicting much secondhand embarrassment on the player. It captures the delight of thinking of the perfectly wrong thing to say. A phrase will stick in Harry’s head (someone refers to the “Wompty-Dompty-Dom Centre,” or seeing a contact mic reminds him of the inspirational boxer “Contact Mike”) and he has to keep thinking about it, and telling the long-suffering people of Martinaise about it, and it starts to be the funniest thing in the world. Odd material calcifies on the walls of his mind and creates an unusual operating environment. The mechanics of thought are themselves jokey: the horn that sounds when a new idea enters the Thought Cabinet, an actual menu of Harry’s fixations, or the typically insulting “copotype” labels, like Sorry Cop and Boring Cop, applied to players according to their dialogue choices.

Another string of metatextual jokes starts with Kim, who endlessly questions your methods of videogame investigation. From the beginning, he gives you kind of a hard time about how you’re playing Disco Elysium: the fact that a locked door exists, he says, doesn’t mean that it’s important. You don’t need to talk to every civilian, collect every random item, or run everywhere, he tells you. (Even if you only walk, Kim will ask why you keep running.)

This is not good advice, because Disco Elysium really does work like the other RPGs that conditioned you to act this way. It has a short list of locations to show you and great surges of text to describe the places it can’t show you. Every locked door is important. (Even the locked door you can’t open, which becomes a symbol of death.) There are no penalties for clicking on everything and talking to everyone, and you will have a better time playing the game if you do so. The time limit is so generous that it amounts to an empty threat. Even the most incidental trash you dig up—the mug with an offensive caricature that you find next to the victim’s clothes—ties back to the case.

Your progress through the game is a process of proving Kim wrong, while also learning about his love of machines, declining eyesight, and sensitivity regarding his former pinball career, as buddy cops do. In the course of the investigation, Harry scrapes himself off the bottom of the barrel, reclaims his symbols of authority, buys better clothes, gets shot (in a criminally rigged skill check that can’t be won), uses the unusual harmonics of his brain to solve the case, extracts a quick confession from the culprit, discovers a cryptid, and (mostly) wins his way back into the good graces of Precinct 41.

Yet this comes as a disappointment after the initial days of the story, which introduce political conflicts and cosmic questions that later fall out of view. Some kind of rain delay prevents the clash of ideologies, and the dock-workers and international capitalists never do battle for the future of Martinaise; whatever escalation follows your skirmish with the Krenel mercenaries is unseen. (Maybe Revachol is, as Joyce said, the city “where the terrible questions of our time will be answered,” but that dialogue won’t happen in this game.) Harry discovers a 2mm pocket of the reality-eating Pale in a church, but the theory that it caused his memory loss turns out to be a red herring. The heaviness of the game’s opening—in a defeated nation on the brink of violence, you play an even more thoroughly defeated man—is too easily dispelled.

The early game floats a number of possible stories that we might be playing through. There’s Kim’s preferred reality, a police procedural about collecting evidence, interviewing logical suspects, and filing forms and reports. There’s a political story that complicates Kim’s view of dispassionate policework: as servants of the occupying Moralintern, the RCM may be asked to act against the interests of the citizens of Martinaise. (The company rep Joyce disavows the rogue mercenaries, so this never graduates to a real dilemma.) There are also the pulp adventures of the “stalwart,” “stout,” and certainly never sorry detective Dick Mullen, of “Dick Mullen and the Mistaken Identity,” to whom Harry suffers many unflattering comparisons. (Despite Kim’s caustic opinion of dime-store detectives, Disco Elysium has a pretty traditional femme fatale, and throws in some “Hardie Boys” too.) And there’s a pervasive melancholy—the “song from another room” sound of British Sea Power’s Whirling-in-Rags theme, the creeping expansion of the Pale explained by Joyce, the hopeless lyrics of Harry’s favorite non-disco tune, “The Smallest Church in Saint-Saëns”—that makes you think it will all wind up a tragedy.

Disco Elysium starts as a story that’s far out of joint with any of these patterns. Framed by Harry’s roiling consciousness, the plot hardly seems able to contain all the fears and jokes and moods caroming around inside it. But in the end everything snaps into a familiar shape: a quasi-mystical cop tale that’s neither procedural nor pulp, but one that feels pretty Hollywood anyway. The politics turn out to be background. The ideology-as-alignment stuff was funny, but this isn’t the kind of RPG where your alignment matters. The outcomes don’t change, even if your dialogue about those outcomes does.

Harry wraps up the case like a regular Dick fucking Mullen, and there is one golden reveal left for the debriefing: we learn that he used to be a gym teacher, explaining his penchant for running everywhere and telling people about Contact Mike. With this last piece fit into place, the strangeness of Disco Elysium is solved; everyone returns to Precinct 41 and to a status quo too boring to depict.

Chris Breault is a writer on the internet.

,