Early in Kentucky Route Zero’s first act, the ambling old truck driver, Conway, finds himself in the main house at the Marquez farm where he sets up a television set for its resident, Weaver Marquez. When the unit is turned on, instead of playing an image on its small screen, the walls of the house dissolve around the pair and the lights drop, shrouding everything in a mysterious hazy dimness. We push in a little closer to Conway and Marquez as an old wooden barn becomes visible behind them in the previously darkened downstage. A scene which might ordinarily have been presented in the form of a cinematic, through some non-diegetic window into a pre-baked, separate world, instead shifts the profile of the existing space, adjusting the scenery and transforming the staging, making the artifice of it more visible, even as it invites you in closer, to see things differently and through a more intimate lens.

Most games tend to take their visual inspiration from the language of cinema. Whether it’s brilliant flares and droplets of water condensation fogging the implied lens of an imagined camera operator, or smash cuts and aggressive angles accompanying the storytelling beats of seemingly every big budget release, games, especially ones designed with 3D engines, rely heavily on the shorthand of film production and the filter of the movie camera lens when it comes to choosing a visual language.

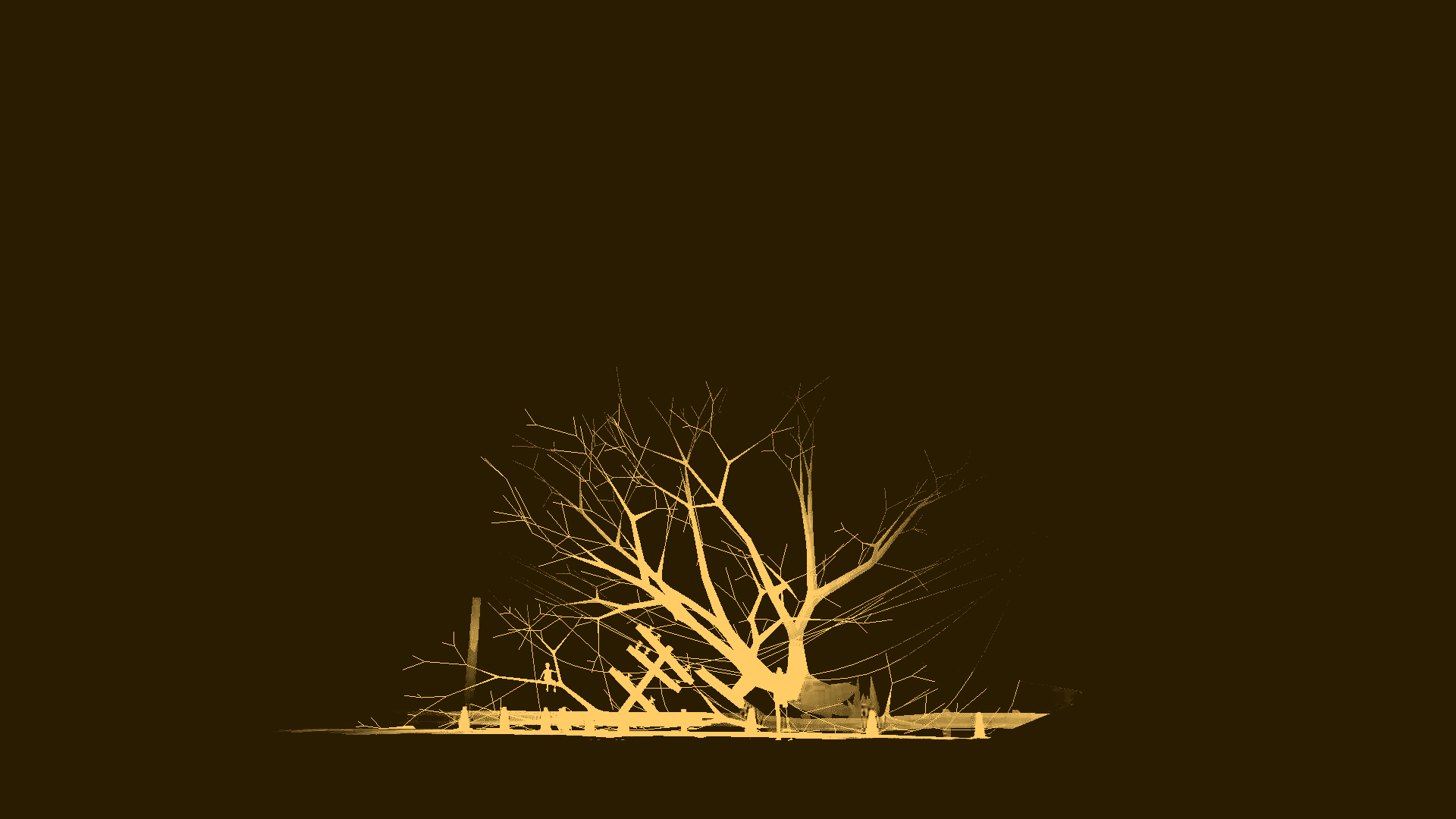

Kentucky Route Zero, on the other hand, seems to take its direction more explicitly from the world of theater. Each of its scenes, while evoking real places, feel constructed from painted plywood and panels of particle board (with seams cleverly hidden and all the tape painted over). Choosing something other than the perfectly textured and lit hyperrealism encouraged by the modern graphics engine, Kentucky Route Zero employs a kind of “2.5D” approach: its three-dimensional spaces evoke reality while being built out of flat artifice and sleight of hand. The sky, rarely visible down in the tunnels and underground rivers of the Zero, could hide hanging spotlights, rigging, and drop cloth, just beyond the action of the center stage. Instead of a disembodied camera tethered to the game’s characters, or one which swivels and pans to reveal every crevice of the map to the player’s inquisitive eye, all motion and framing in Kentucky Route Zero is preconceived, purposeful, and done with rigid restraint. Moving between spaces recalls the scene changes of a play, with the fabric and architecture of the previous scene dissolving and falling away as new layers move resolutely into the light.

The manner in which these scenes are set, and the lack of the distance that comes from seeing everything through a camera lens, encourages a feeling of closeness and intimacy between the player and the principal characters of Kentucky Route Zero. It also establishes a tension between the handworked roughness of the game’s visual style and its big literary themes of scarcity, dashed dreams, and social exclusion. In The Devil Finds Work, James Baldwin defines the “... tension between the real and the imagined” as something unique to the theatrical experience. He adds that in the theater, “One is not in the presence of shadows, but responding to one’s flesh and blood.” Kentucky Route Zero sits squarely on the threshold between the real and the imagined. How fitting it is then, that it presents the liminality of this uneasy position through theatrical trappings so well suited to communicate the tension it produces.

One of the ways this tension surfaces is through the game’s characters, who, like the set-piece architecture of their environment, contain considerable depth while also functioning as cyphers meant to personify broader ideas. There’s Conway, who represents the plight of the working class, the aging, and the addicted. The specific beats of his life story spell out a relatively universal fable: a man unable to find his place, glomming on, as a result, to any port in a storm. He also transforms, over the course of the game, into a glowing neon skeleton, limbs buzzing with static as they bend. Over time, he ceases being a performer and becomes a part of the set.

There are also the traveling musicians Junebug and Johnny, who are, by nature, performative beings. Once mechanical laborers, now artists by trade, they turned to the theatrical to gain access to that flesh and blood connection Baldwin speaks of. Their key moment is in Act III, during which they perform a song in a bar that lifts its rafters and exposes the starry night sky above. Their lyrics vary depending on lines the player chooses, giving their performance a branching and multi-varied texture. This moment readily evokes Baldwin’s description of the theatrical experience where “No one can possibly know what is about to happen: it is happening, each time, for the first time, for the only time.” He continues, adding “I had never before, in the movies, been aware of the audience: in the movies, we knew what was going to happen, and, if we wanted to, we could stay there all afternoon, seeing it happen over and over again. But I was aware of the audience now. Everyone seemed to be waiting, as I was waiting.”

Audiences are an implicit part of many of Kentucky Route Zero’s notable scenes, particularly its performances. When Junebug and Johnny croon their number at The Lower Depths bar, Conway, Shannon, and Ezra serve as their audience, framing the performance from the foreground. The Lower Depths actually makes its cameo in the preceding interstitial chapter The Entertainment, where it serves as the setting for a student play. There, the scene is witnessed not through a camera but through the eyes of a silent extra, who sits between the main performers and a darkened audience lounging on risers in the back. We can just make out their faces, and their state of attentiveness, which changes throughout the course of play. Later, in the game’s fourth act, the player can choose whether to experience a theremin show alongside the artist herself or from the vantage point of the crowd below.

Including this interplay between performer and audience lends Kentucky Route Zero not only a sense of theatricality, but one of inviting closeness, of casual belonging. Inside the theater, things tend to feel more intimate, the flesh and blood of those on stage reaches out and touches the audience, who are more visible because they are more explicitly invited in. That these audiences are more present makes them feel more important than the audiences for films, which play the same to empty houses as they do for full ones. The spaces that make up Kentucky Route Zero feel more open and alive because they acknowledge the indispensable give and take that sharing one’s art involves, and which the theater draws out in sharp relief.

In including audiences, onlookers, casual observers of a stage play, a group of friends exploring a gallery, a town of houseboat dwellers stepping out onto the docks for a makeshift concert, the game also includes us, the players. We are invited to look, to share the vantage point of those who are also there to bear witness. “... The camera sees what you want it to see,” according to Baldwin; it is an internal eye as much as it is an outward one, and it does not allow for the gazes of others to invade its own point of view. Kentucky Route Zero, in providing for other sets of eyes, in establishing a context of observation, diversifies and disassembles this overpowering focal point. We are invited to watch but we are not allowed to define the bounds of what we are watching, as we would were we seeing through a camera, in total control of capturing a scene.

As surreal and magical as the world of Kentucky Route Zero can get, with its ghosts, its skeletons, and its building-sized eagles, it remains a crafted place, one which belongs to the hardwood surfaces, the stark lighting, and velvet curtains of the theater. As such, it never feels out of grasp or ephemeral, but grounded and intimate. Its scenes are spaces I can envision walking into, where I could take a seat on a rickety bar stool and feel transported by the passion and enthusiasm of the different artists and musicians lending a bit of their light before they pass through to the next spot. The game’s moody geographies may be pieced together from places I’ve never been mixed with places that don’t exist, but they still manage to feel familiar, built from the same rough-hewn blocks as everything else, paint on wood, cloth draped over crossbar; constructs erected to communicate ideas that are, themselves, just as wide-ranging and universal.

***

Yussef Cole, one of Bullet Points’ editors, is a writer and motion graphic designer living in the Bronx, New York. He writes primarily about how video games intersect with broader cultural contexts such as class and race. His writing stems from an appreciation of the medium tied with a desire to tear it all down so that something better might be built. Find him on Twitter @youmeyou.