During one of the interstitial scenes that take place whenever your character, Artemy Burakh, dies in Pathologic 2, the puckish theater director, Mark Immortell, raises the topic of exhaustion. “Tell yourself, 'I’m exhausted, I can’t take it anymore,'” he admonishes. "Take pity on yourself and stop in time.” He continues: “Such a paradox! To admit you’re tired—is that a step toward death? A surrender? An admission of your natural limits? Or is it a step back to whatever happens before death?”

To play Pathologic 2 is to negotiate constantly with limits; to explore that narrow space between normal life and harrowing death. To play it is to measure how much punishment you can take before you put the controller down, how frustrated you can get with its systems before you stop acting with cold, min-maxed precision and begin to blunder hopelessly around its stage, tearing your puppet, Artemy, to shreds in the process.

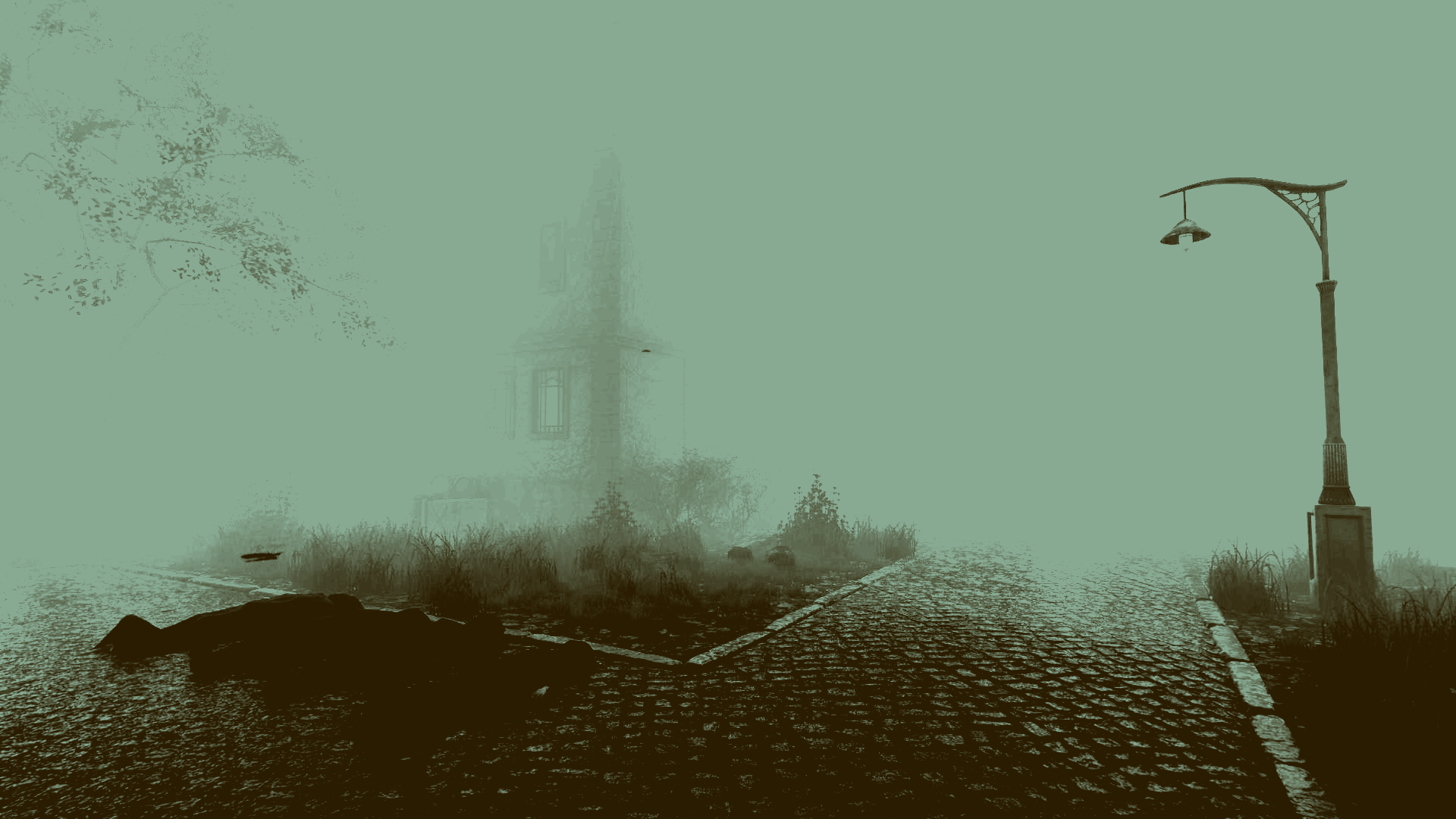

To write about Pathologic 2 is a similar exercise in limits. At least it has been for me. The game came out last year, when the word “pandemic” barely even brought the distant specters of SARS or Ebola to American minds. The game plopped its disfigured shape, full of desperate resource management and oppressive sickness (picture the malaria mechanic of Far Cry 2 pushed to a cartoonish maximum) into a gaming scene largely disinterested with its challenges and its dour, depressing world. I played it when it came out, at least enough of it to want to write something about it. I wanted to dive into the clever ways it uses the extreme setting of a town suffering from a plague to expose the broad hierarchies of society: the ways privilege and wealth determines who survives and who doesn’t during times of mass sickness.

The topic was mostly stuck in the domain of the theoretical, and the essay stuck in my drafts, until 2020 happened, and COVID-19 with it. I realized I had spent far too much time last year reading books about past plagues: Bubonic, Choleric, Influenza, Malaria, excising quotes and passages that might feel relevant today, only to see the world around me rise with an alarming speed into far greater relevance than my research could ever provide. The horizon rose up and swept past us all, and one of the many, many things this tremendous wave upset was my “big essay idea” of 2019.

And now it’s June, over two months into a shakily maintained social isolation, currently split open by justified mass protest against police violence. And I still want to talk about the game. I still want to think about it. I think more of us would be benefited by a prolonged encounter with it. But I am also deeply exhausted. Like Artemy, stalking the streets of the town, searching the trash cans for loot and bodies for blood and organs, I’m stretched thin. Not, by any stretch, by the same kind of grisly necessity, but in the overwhelming piling on of anxiety, of worry, and of responsibility that we all are forced to grapple with today.

What is ironic is that, in addition to predicting every other aspect of our experience with the pandemic (children aren’t affected, “essential workers” are sacrificed for the broader good, the transformation of public places into triage units, the flailing authoritarianism of the state, and so on), Pathologic 2 manages to model this precise form of exhaustion, the general shape of this pandemic-induced stress. Because, despite the conversations around difficulty that colored Pathologic 2’s release, it is not so much a game about difficulty as it is one about dealing with, and being humbled by stress. Where other hard games offer challenges to the player to overcome and thus prove, and feel good about themselves, Pathologic 2 uses its challenges to slow us down, to force us to think about what we’re doing and why we’re even doing it.

Writing is always difficult, a steep hill to climb with the promise of an exhilarating slide down the other side. But trying to maintain discipline the past few months has been a unique challenge all its own. The television show I creative direct, Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj, is back on Netflix, with our team trying to stay organized despite being an operation that once existed in one office, now spread across sometimes hundreds of miles. These new necessities, and the numerous other responsibilities my position carries, only seem to have increased in this new reality. So the tension of balancing roles, of keeping checklists oriented in my head as I jump from writing to designing, from doing grocery runs to hopping on video calls, has been greatly exacerbated by COVID-19. As I sit down to write this piece about a game which has so much to actually say about pandemics, what I wind up thinking about is what it has to say about the uneasy weight and sometimes heavy toll of leadership.

The typical image of a leader is a confident, cishet white man. Someone assured of their place in the world, no visible insecurities rising up to prevent them from making bold and effective decisions. This is the (false) model I’ve often felt pressure to contort myself into, out of a want for many other clear examples. It’s the model Pathologic 2 seems, at first, to embrace. Artemy is young and clearly capable, a man trained in the city, come to rescue the helpless townsfolk of his backwater hometown. But it isn’t very long before the game unceremoniously rips the rug out from under this shiny and deluded fantasy.

The townspeople of Pathologic 2 laud your presence, while sabotaging you at every opportunity. They trade with you during the day but rob you at night. Stores raise their prices as the disease worsens or switch currencies altogether. The town’s leadership leans on you for help while providing you with barely enough resources to keep yourself alive, let alone others. All of Pathologic 2’s systems conspire together to twist your own ego and false sense of heroic duty against you. It dangles moments of altruistic action, juicy bait for the player accustomed to games that present a straightforward, signposted path toward just and benevolent victory, only to yank them away as a lesson in humility, provided you have the honesty to “admit you’re tired …” as Immortell puts it.

Pathologic 2 certainly hints at the possibility of an ideal playthrough, provides glimpses of runs where no one dies on your watch; runs where you proudly fill your father’s shoes and stitch back together what he had previously torn apart. But, for most, these runs are fantasy, a falsely shining beacon floating above streets drenched in the blood of your mistakes and blunders. And expecting this level of perfection in a game so invested in showing us the ways life is messy and frayed is downright self-defeating. Instead players should come to terms with the exhaustion that Immortell alludes to; an exhaustion born of refusing to accept one’s limits, largely because games often tell us that we usually don’t have to.

After all, that Dark Souls boss may seem impossible at first, that Diamond rank in Overwatch may feel frustratingly unattainable, that platforming run in Celeste might give cause to toss our controllers in rage, but with enough patience and dedication, these challenges flatten and become rote, attainable. They are systems designed to provide dramatic tension but also assured victory. They are not reflective of the way the world works, they are theme parks meant to reflect the way we want it to.

Pathologic 2, instead, seeks to undermine the institutions and hierarchies which we hold dear, just as real plagues and pandemics so often do. As in the real world, no matter how heroic or determined the doctors, it takes far more than sheer will to save lives and help people. It takes resources and social systems designed around infrastructure and effective safety nets rather than corporations and capital. And no matter how steadfastly the rest of us attempt to continue to stay positive and productive, the weight and necessity of survival will continue to drag at our heels and pin down our backs.

Admitting that we are tired is not an admission that we are dead, but a necessary reckoning with being human. Part of the process of the last two months has been realizing I can’t do everything, nor should I push myself beyond my limits just to satisfy poorly-defined expectations around leadership (usually ones I’ve built up entirely on my own). Recognizing our limits can be a way to heal, an option that isn’t really offered to Artemy in Pathologic 2. Ignoring them means running aground in a sea of overlapping and overwhelming responsibilities; a warning to those who think that stubborn obstinancy will save the day, who believe that a leader can barrel through life’s obstacles without losing pieces of himself in the process.

***

Yussef Cole, one of Bullet Points’ editors, is a writer and motion graphic designer living in the Bronx, New York. He writes primarily about how video games intersect with broader cultural contexts such as class and race. His writing stems from an appreciation of the medium tied with a desire to tear it all down so that something better might be built. Find him on Twitter @youmeyou.