"The Good Times

The Bad Times

They Exist Together

Intertwined."

— Gwen, Spiritfarer

[CW: Suicidal thoughts.]

The last time my mother came to visit us, we had a screaming fight in the car. I was slowly pushing north through New Jersey turnpike traffic, knuckles straining against the steering wheel, and yelling through gritted teeth at her reflection in the rearview mirror as we argued bitterly over the wasted car trip we had just taken to fill out incorrect paperwork for her house back in Tunisia, where she spends most of her time.

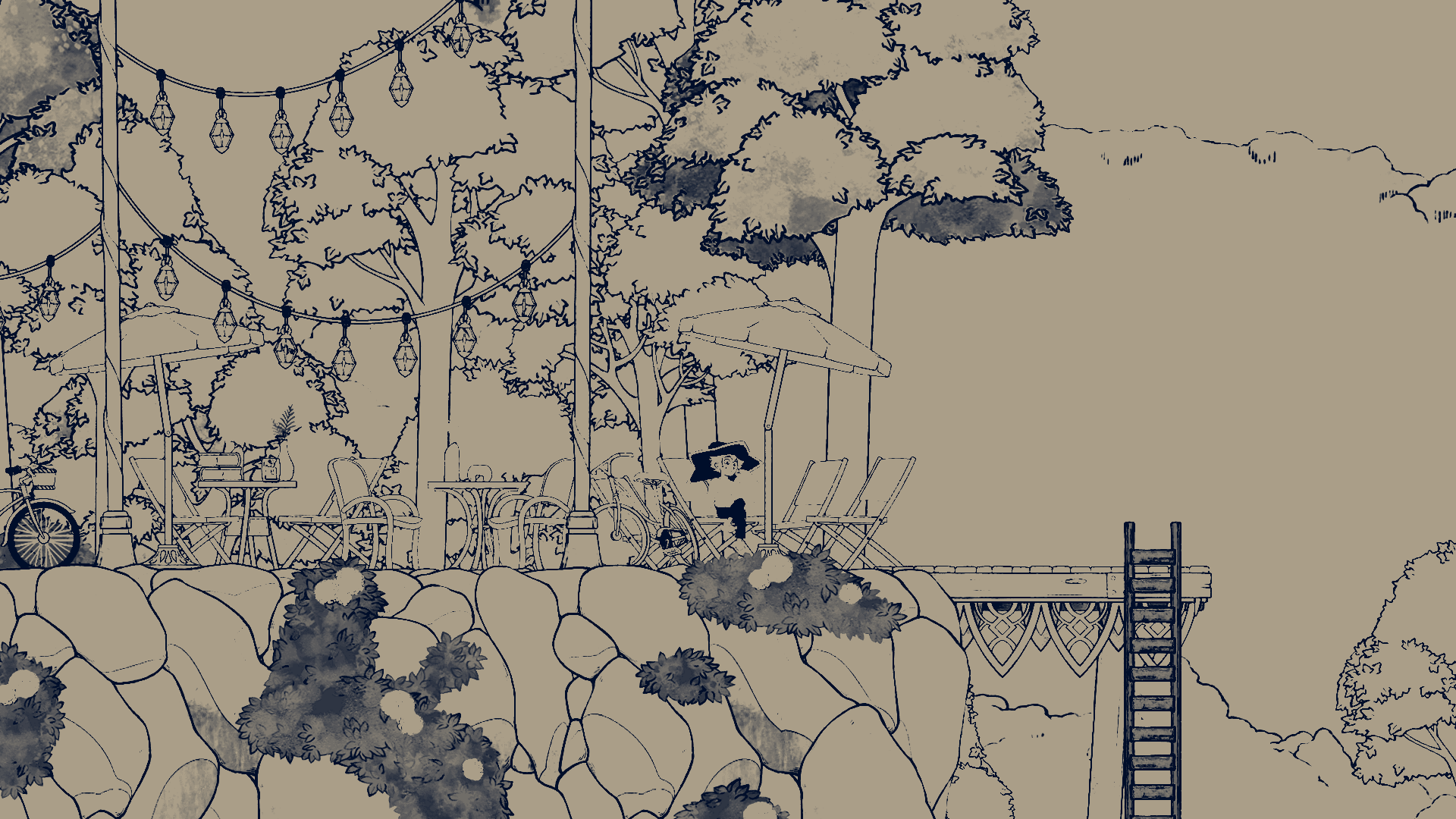

Time in Spiritfarer is divided up into days. The barge which the game’s main character, Stella, uses to ferry numerous spirits to their afterlife through a gateway called the Everdoor, can only travel during the day. As the sun makes its way to the horizon, I race around the deck, trying to manage ten chores at once: feeding sheep, planting crops, fishing for supper, and plotting out my next destination. All the while, my spirits, some doddering and absent minded, some bitter and occasionally cruel, clamor for my attention: a meal, a hug, a willing ear.

I often repeat the aphorism to anyone who will listen: my relationship with my mother operates on a timer. Though I love, and deeply appreciate her, we cannot spend more than a single week together without disintegrating into knockdown drag-out, emotionally draining confrontations. Our relationship resembles the volatile structure of an unstable elemental compound, floating uneasily along until some hidden spark lights the whole damn thing aflame. Then, her diminutive, five foot tall body will tense up before unleashing a rage better suited to a hulking giantess, or a brown bear stood on its hind legs; teeth gnashing out a desperate plea for affirmation and unchallenged love.

Though mostly pleasant, the spirits of Spiritfarer are sometimes inclined to withdraw into themselves, rejecting the help I offer, even occasionally disappearing off of the boat for extended periods of time. The first spirit I encounter in the game, Gwen, is a stately-looking deer who chain smokes from a holder and is picky with her food. Late in her journey, overwhelmed by familial trauma, Gwen disappears from the boat. She can be found outside her childhood estate, where she is considering taking her own life. I manage to talk her off the figurative ledge and convince her to return to the ship. Only in embracing my guidance, in letting her worries melt under my care, can Gwen complete her journey through the Everdoor with some measure of peace in her tortured heart.

Sometimes I feel relieved that my mother and I live on separate continents. Our physical distance from each other allows us to correspond without the strife and tension born out of closeness, and we can generally control when and for how long we are willing to enter each other’s orbits, keeping the time we spend together that much more peaceful. But as she gets older, time becomes less an instrument with which to manage our relationship than a precious resource we seem unable to keep from slipping through our fingers. I can’t help but worry constantly about her, about what I can do for her from all the way on the other side of the ocean. I run through scenarios in my head: if she fell down or got sick, who would be around to help her? Would I be able to communicate with nearby family members in my shaky French or non-existent Arabic? How much would last minute flights cost? Helplessness and anxiety inform my thoughts when she is away, just as impatience and anger take over when she is near.

Alice is a hedgehog spirit who grows older and weaker before my eyes. Ordinarily she is a sweetheart: she often bakes pies for the other passengers and lets me use her wardrobe to try on clothes. During our final outing together, we clamber up the piers of the windswept, frosty island, Nordweiller. There, she recounts vivid memories of some half-remembered romance novel until she suddenly exhausts herself and needs to be taken home. Like a switch, it’s as if her demeanor has changed completely. She turns on me, huffing: “Has anyone told you how smothering you can be?” before storming off to her cabin. She doesn’t apologize the next morning, nor ever mentions it again. Eventually she grows too weak even to travel the length of the deck, and she forgets Stella’s name, thinking she is some family member instead. Swallowing the bitterness of this pitiful transformation, knowing how sick she is, I help her get around the ship and later, bring her to the Everdoor. It’s only then that Alice finally remembers who Stella is and is able to thank us before disappearing into the night sky.

During one of my recent visits to Tunisia, my mother came out to meet us at the airport. Still sluggish from the long flight, I stooped over to hug her, wrapping my arms around her tiny shoulders. She felt small and brittle. Later she lambasted me for the weakness and lack of warmth in the hug: “You didn’t even kiss me on the cheek, what’s wrong with you?”

In Spiritfarer, it isn’t difficult to know how to behave with the different spirits under your care. Their likes and dislikes are fastidiously recorded and easily accessible. Some spirits love a hug, like the gregarious old frog, Atul or the playful young Stanley, who will jump up and wrap his arms around me without a moment’s hesitation. Other spirits spurn physical affection. Elena, the ex-schoolteacher, still affects the rigid institutional distance and keeps me at arms length up until the end. But the comfort is there, in the knowing: that, say, casseroles and pies are five-star meals for some and carb-heavy trash for others. It’s nice to know that if I build you a house and outfit it with three specific improvements, I’ll have you on my side, dear spirit, forevermore.

No matter how hard I study, I find myself a poor student at my mother’s tests. Perhaps it’s in the unsteady lines of her silhouette. Despite a lifetime, I cannot read her: a small, harmless woman at times, and a raging behemoth at others. Her spirit is strong and was built to withstand all the journeys she has taken, the oceans she has crossed, again and again. But where does that leave us? Were she a spirit in my care, I could learn her secrets, her desires, her comforts. But the rage repels me, keeps us apart. Our ships, for the moment, travel different seas.

Perhaps I should look to take my cue from Stella. The mood of the spirits swell and break like the waves your boat slides interminably through, but Stella is a rock, a tree with mile-deep roots. She beams through the indignities, through the mercurial moods and petty grievances. She guides each spirit to their fate with a hand as effortlessly firm as it is soft and comforting.

My mother’s spirit resists easy answers, and doesn’t provide readily mappable likes or dislikes. But, like Stella, while I cannot control the actions of those I care about, at the very least, I can control my own; provide comfort when it’s needed and distance when it is asked for. Someday soon, I will need to find a way to close the distance with my mother, find a way to care for and comfort her, in spite of the heat and the flames. After all, getting along with family means recognizing that the good and bad are irrevocably intertwined. And the bond one makes with another’s spirit must encompass all of it, if it is to last until the very precipice of death.

***

Yussef Cole, one of Bullet Points’ editors, is a writer and motion graphic designer living in the Bronx, New York. He writes primarily about how video games intersect with broader cultural contexts such as class and race. His writing stems from an appreciation of the medium tied with a desire to tear it all down so that something better might be built. Find him on Twitter @youmeyou.