This article discusses plot points from the entirety of Outriders.

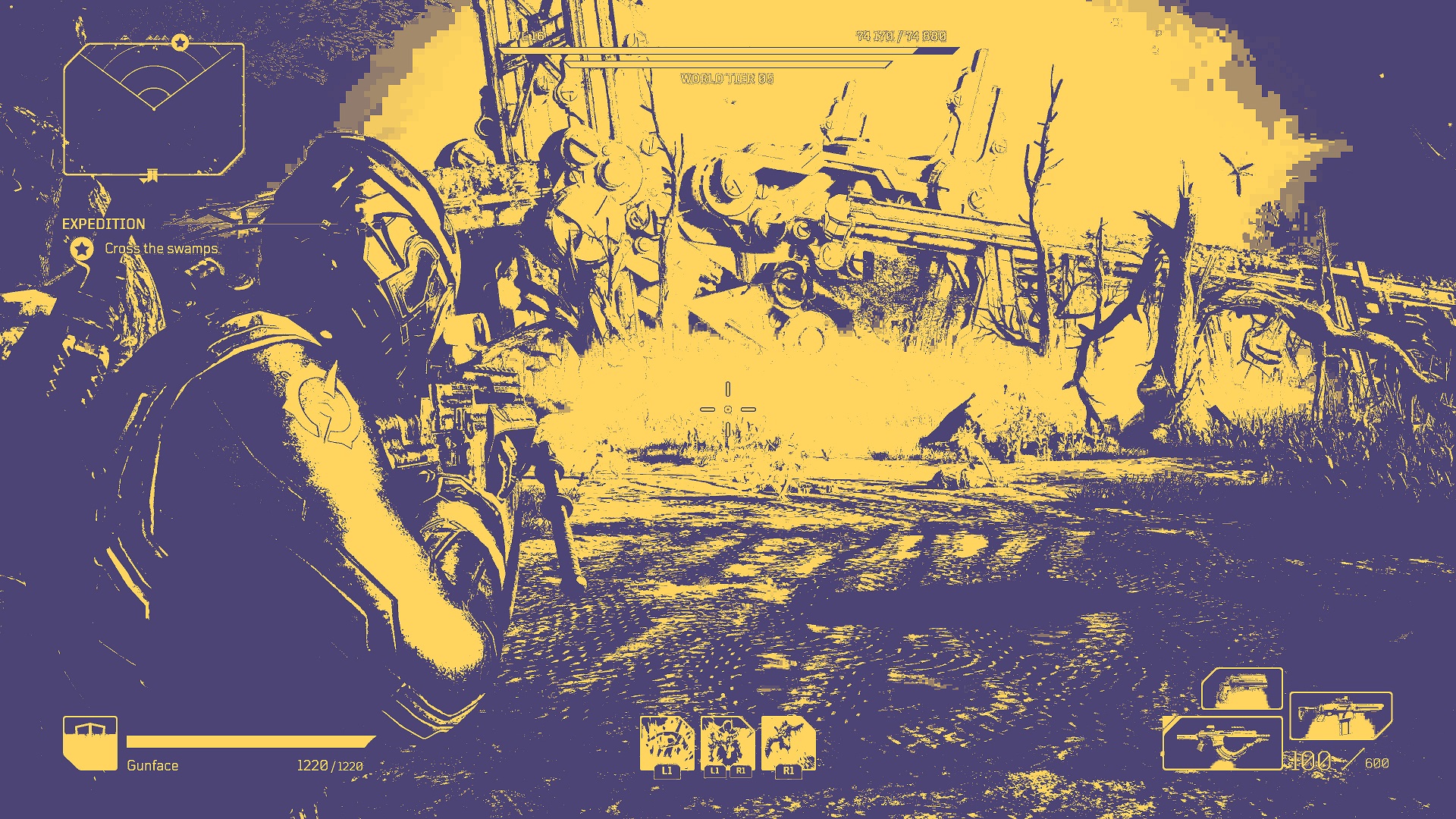

People Can Fly’s Outriders can accurately be described as a "looter-shooter." This means it's entering a scene which already falls under the long shadow cast by subgenre progenitors like Destiny and Borderlands. True to this form, playing Outriders involves running around hub areas, clearing them of various enemy types, collecting the spare weapons and armor they drop, and either grafting them onto your little clay golem or breaking them down into their component raw materials. It’s a familiar cycle and Outriders sits uneasily within it, knowing full well who it borrows from, and knowing that we, the audience, know too.

Your protagonist also enters into (more than one) existing cycle themselves. Outriders' narrative kicks off with the last remnants of humanity traveling by way of ark ship to the planet Enoch. With Earth functionally gone, they’ve come in search of a new Eden to colonize and make their own. But they’re too late. Enoch has already been touched by the greed and selfishness of humanity. You learn later in the game that another group has preceded you and, to cram a lot of plotting into a single summary, fucked everything up. The dream of new beginnings is thus swiftly trampled and humanity falls into the same old pattern of endless conflict over limited resources.

While this is well-trod narrative territory, it’s still eerily relevant to the current political period. Around the world, and to extremely varying degrees, humanity is slowly making its way out of the century-defining pandemic caused by the COVID-19 virus. The past year has seen incomprehensible levels of death and suffering, overseen by political forces too blinkered and fundamentally broken to come anywhere close to easing the pain. In America, the person who oversaw most of the botched pandemic response, Donald Trump, has been shoved deep down the memory hole, his name a curse on our lips and his legacy rarely mentioned—easier not to have to reckon with the festering wounds his reign leaves behind. Our new administration sits anemic and listless on the throne. No one on either side of the political divide has much enthusiasm for the machine of governance anymore. We have all learned very difficult and dispiriting lessons from past experiences, from old cycles.

We were told that American exceptionalism and individualism would save us, that free thought and the open marketplace of ideas would naturally and inevitably drive progress forward. We were told to vote with our wallets and at the ballots; to line up for hours so that we could stave off fascism and terror, just so we could get sneering neoliberalism and technocracy in its place. It has become more and more difficult not to feel detached and powerless in the face of the massive systems and processes which have total control over our lives.

This state of affairs, which plagues Americans and, in another form, the Polish developers of Outriders, finds ready reflection in the world they’ve created. Enoch’s nascent human colony is barely hanging on, divided and embroiled in self-destructive conflict. The surviving settlers, themselves the privileged few who made it off a poisoned Earth, find themselves trapped between the callous remnants of Earth’s government, the bloodthirsty insurgents trying to tear it all to pieces, and—just so things don’t get too dull—cataclysmic lightning storms called anomalies.

Into this mess wanders your Outrider, whose god-like abilities allow him to step free of these disastrous cycles. His bullheaded and arrogant individuality provides a perfect avatar for the player’s needs. “Only one like you could lead them to a future,” the similarly superpowered Seth informs you in a cutscene. “You are to be the shepherd … ”

And so we move forward, pushing towards this world’s “frontier.” We follow the Outrider’s prescribed path to a hoped-for place beyond the anomaly, some kind of escape from the walled-in hell of the original settlement. And even when it’s revealed that there’s no “there” there, we keep going anyway, keep up the forward momentum. In our own lives we act similarly. We keep logging on and showing up for work, keep attending classes, handing in assignments; we stay functioning and productive. We follow the prescribed path forward even as it becomes less and less clear that it will take us anywhere good, anywhere at all.

After the last mission in Outriders, once your team succeeds in contacting the dormant ship Flores in orbit and sending its precious supplies planetside, you turn to find a ragged band of survivors who have been following you all the way from the original settlement. They all chose, in spite of the dangers, to place their hopes in the Outrider’s path. Heroically, biblically, his silhouette appears over the crest of a sand dune, this world’s own Lawrence of Arabia. But he never knew where he was going. The destination doesn’t matter to him, just as it certainly doesn’t really matter to the player. We spend the game knowingly, for the most part, traveling down a literal road to nowhere; one which terminates in a desert wasteland littered with the dried corpses of past colonizers lying alongside their unwilling subjects.

Even as we delve deeper into these hellish landscapes, witness sick and twisted depravity, stroll through set-piece allusions to some of humanity’s most foul historical events, we wind up choosing violence again anyway. It’s obvious that our people are doomed (if they can even be considered our people, detached as the Outrider is) to scrabbling futility for sustenance in a contaminated and spiraling ecosystem, but we shrug it off; we pick up the weapon with the higher numbers and make more bad guy heads erupt in colorful splashing geysers. Sick.

What’s in it for us? What can we extract? In systems with minimal trust for authority figures, in the breakdown of social norms following traumatic natural disasters, these often become the only questions which matter. Isolated and alone, we make more selfish decisions than we might have otherwise. In the midst of COVID-19 surges, we flout masks and crowd around brunch tables; we cut in line to get our vaccinations early, we become rabid capitalists, speculating on Gamestops and cryptocurrency-backed art—and the world burns all the while.

Amidst these flames, in this period of utter political exhaustion, contending with so much malaise and nihilism, it’s easy to act in more self-involved ways. It’s easy to live, as the Outrider does, alone, but powerful, untouchable. The promise of the looter-shooter is the colorful and outrageous fun of ultra-violence. How convenient then that their worlds are so often broken in such a way that this is the only kind of fun to be had. How convenient is it that our own society is divided in such a way that we allow wreckless self-fulfillment, rather than collective action to drive us?

It’s understandably difficult to resist the cynicism, the creeping defeatism of the present. It’s tempting to fall back into the old cycles, the empty grind in search of something more, which these looter-shooters so readily symbolize. We find as much comfort in the numbing disposability of their design as we do the interchangeable markers of ambition in our own lives. In the face of the unbearable present, it’s hard not to search for some temporary imagined reprieve just down the road.

But that destination is as much a misdirection as the final terminus—a dead ship floating on a river of sand—of the Outrider’s journey. It is imperative not to throw your hands up and decide that the planet is ruined anyway, that the poor and marginalized are screwed anyway, that there is nothing left to do but look after your own interests, hoard your own loot. Instead, why not make an effort to move beyond the inertia of helplessness and inaction? Why not aim to lead others as the Outrider cannot? Not in search of distant salvation but in the interest of fixing what is broken in the here and now.

***

Yussef Cole, one of Bullet Points’ editors, is a writer and motion graphic designer. His writing on games stems from an appreciation of the medium tied with a desire to tear it all down so that something better might be built. Find him on Twitter @youmeyou.