Deathloop, like all games in the Dishonored series, is about History. I know what you are thinking, but there are no mistakes in that sentence. Yes, Deathloop is a Dishonored game (hiding in plain sight, appropriately enough) and yes the History we are talking about here is the one with a capital H.

It’s forgivable if you are confused. Deathloop, after all, has been framed as Arkane’s “next big thing,” its escape tunnel from the exceptional but underperforming (by publisher Bethesda’s inflated standards at least) Dishonored 2 into the wide plains of AAA multiplayer/singleplayer hybrid development. Unsurprisingly, this narrative might be more of a PR game than it is a development truth. Arkane don’t exactly hide the connections—there’s a literal smoking gun, which antagonist Julianna calls “part of history:” two duelling pistols, with their “original oil cartridges” directly taken from a duel in Dishonored’s “Lady Boyle's Last Party” level presented at the end of the game with the purposefulness of someone delivering a final twist. But to be honest, if you’ve been paying attention the game is given away far before then.

Where should we start? There’s the “heritage gun,” a sawn-off bolt action sporting an “imperial armories” sigil showing Dunwall’s iconic clock tower and a Dunwall serial number to match. There’s the “treasure of the ice,” an ancient creature unearthed from Blackreef’s permafrost which looks straight out of a Dishonored museum, and certainly isn’t any known creature from our world. How about the taped transmission of Dishonored’s “Drunken Whaler” sea shanty, recorded by spies on Blackreef? All these have been lumped together as easter eggs of course, much like the arcade machines that dot the games locations and reference all the games in Arkane and Bethesda’s history. But even more telling than these “references” is the material reality of Deathloop’s island of Blackreef.

Arkane have always been master worldbuilders, layering up their locations with distinct eras, each with their own materiality and aesthetic, like differing strata of rock in a geological record. Blackreef is no different, and this strata speaks of a continuity between Deathloop and Dishonored. Updaam, the town at the centre of the island, is filled with Dishonored furniture and architecture, in what feels like an incredibly self-aware case of so-called “asset reuse.” What was contemporary design in the Victorian grandeur of Dunwall or the colonial salons of Karnaca has now become antique in the world of Deathloop. In fact Arkane seem to be playing a clever game with players, knowing that such obvious continuities can easily be labeled as “asset reuse” and dismissed just as readily as the fourth wall-breaking “references” and “easter eggs” mentioned above. Equally, the game’s entire supernatural power system, and the way it fits into its world, is another startlingly obvious connection which is easily dismissed because of expectations. Arkane know players and critics expect an Arkane game, which means a certain suite of powers, allowing them to work with Dishonored abilities such as “Blink” (now "Shift") or “Semblance” (now "Masquerade") without necessarily exposing Deathloop as a continuation of Dishonored’s world.

These powers are fascinating because they reflect the shift from the “occult magic” of Dishonored to the “occult science” of Deathloop. While the powers in Dishonored are gifted by the Outsider, a devil-like character who offers faustian pacts to chosen individuals, those in Deathloop are created in experimental laboratories, in places like Blackreef which houses some form of quantum anomaly. In fiction, this shift is a direct result of the final events of Death of the Outsider, the last Dishonored game before Deathloop, where the player chooses to kill the Outsider, separating the powers of the “void” from a sentient being, and unleashing it as a force upon the world, a force which 100 years later, is being explored through scientific experiments in Deathloop. Out of fiction, this shift seems to also represent something of the shifts experienced in the late 19th/early 20th century, where previously unknowable, even magical forces became identified, studied, captured, and harnessed.

This is where History comes in, because as a series Dishonored was always a twisted mirror held up to imperial pasts, filtering them into a different universe that somehow followed the same patterns of extraction, colonialism, and subjugation. Dunwall, in its hybrid of London and Amsterdam, is designed to be the epitome of a colonial metropole, and its struggles with plague, resource extraction, and poverty are pulled directly from Victorian history. Arkane have always been very direct about this, especially in their periodisation of their fictional world, the 1830s to the 1850s. These three decades saw the consolidation of British Imperial power and the economic and social effects of the Industrial Revolution, as London wrestled with poverty and disease even as it positioned itself as a global centre. The fact that Dishonored’s fictional world seems to be tracing the same developmental path as our own is a telling one, and puts the series in direct engagement with History, that is the precession of dates and events that exist to provide continuity to nations, people, and movements. Both Dishonored games concern the shift from seemingly noble monarchies towards facist regimes, reflecting the transition of nation states from feudalist to capitalist structures, and in doing so engage directly with a historical materialist view of social progression.

Deathloop meanwhile, carries this same universe forward into the 1960s, still mirroring the procession of events that created the material conditions of that period, but from the other side of this strange, magic-infused looking glass. Colt is the ideal agent to carry us through these massive shifts in history, and is also another case of Arkane showing its obsession with the significance of dates. To put it simply, what could be a better symbol of encroaching modernity than a character called Colt born in the year 1911? Here is a man named after a machine of efficient violence, whose namesake doesn’t even exist in his world. Colt, like a Dishonored universe Forrest Gump, is hinted to have passed through key moments of history, with Deathloop mentioning the “Siege of Havrilad,” a battle which by name alone evokes the Dishonored universe’s equivalent of a Second World War. This war, also alluded to by the fortifications and military documents of Blackreef (which visually and narratively align with the WW2 bunker architecture created during the British occupation of the Faroe islands), seems to have resulted in Dishonored’s Russian-inspired Tyvia breaking off from Dunwall’s Empire of the Isles to form the “Motherland” mentioned and referenced in so much of Deathloop’s architecture and lore. It is Colt too, who is part of the first experiments on Blackreef, those which aesthetically and historically seem to be eluded to as a Sputnik moment in history, with the look and name of the vessel Colt rode into the first timeloop, the “Raketoplan”, borrowing from contemporary Soviet tech and iconography. But while outer space was the vast unknown that superpowers were racing towards as the 1950s became the 1960s in our universe, in Deathloop and Dishonored it is the “void,” that powerful pocket dimension—once possessed by the Outsider, but now released upon the world by his death—that is driving History.

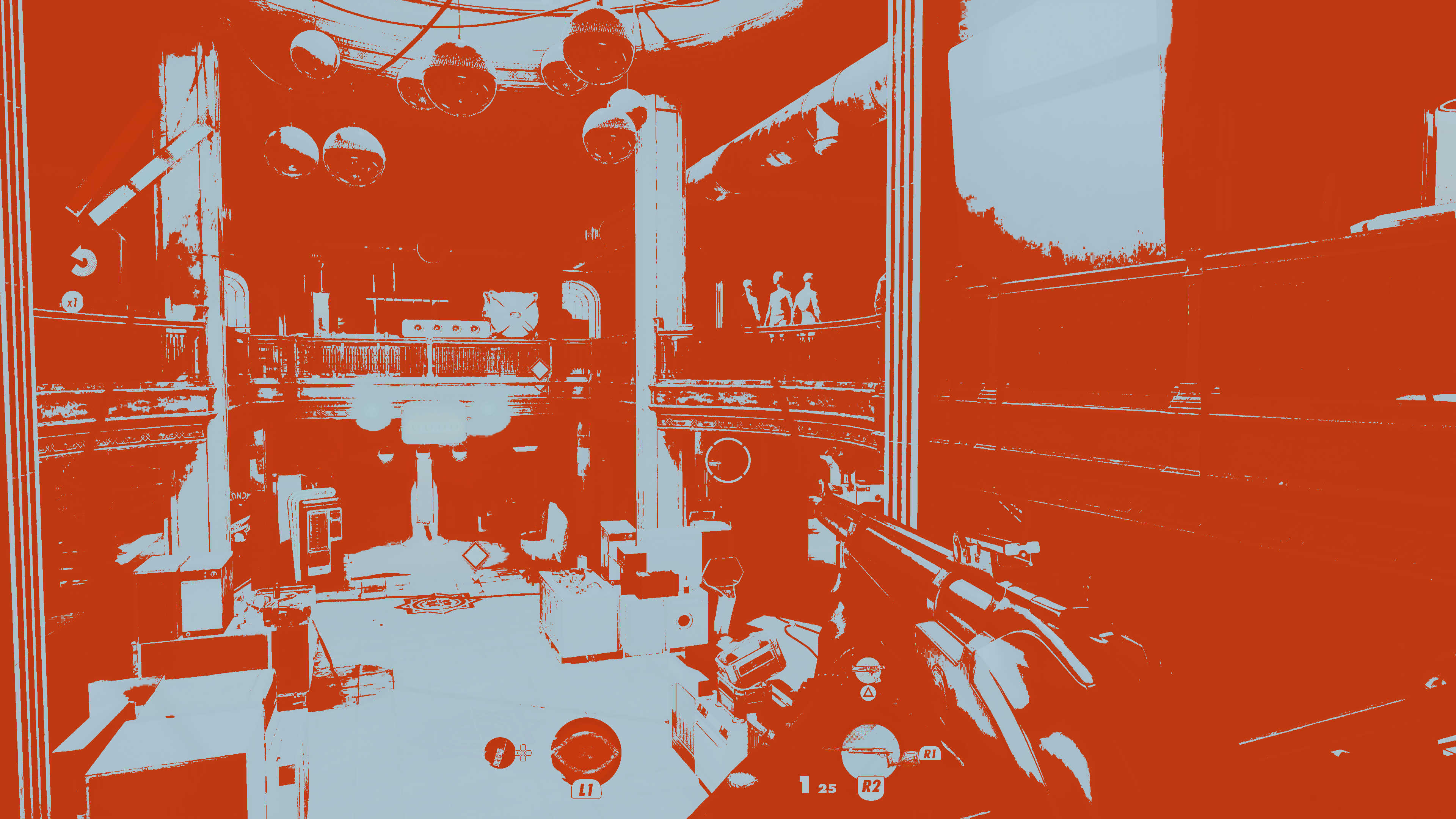

Once you understand this, everything in Deathloop falls into place. Visually and spatially, it straddles the 19th and 20th centuries with grace, its Hebridean-style fishing town abandoned then repurposed by early modern military architecture before being overlaid with the futurist sensibilities of post-war liberation. While the raygun and pop art aesthetics of the 1960s that make up a big part of Deathloop’s inspiration took their cues from the space race and that era’s vast technological leaps, the game’s own take on this era draws instead from the “void.” So we get the same pristine and colourful visuals, but marked instead by an obsession with an ever present “other” space. It is everywhere in Blackreef, from the incidental magazines (Sensate, Elsewhere’s Edge, and Delirium Magazine) to the work of antagonist Harriet Morse, who speaks of “The Great Beyond'' in much the same way the artists and writers of the Dishonored games wrote about or depicted the void. Arkane go out of their way not to just mirror and distort the aesthetics of the 1960s, but to mirror and distort the material conditions that created those aesthetics. In Deathloop, psychedelic art, for example, is not an extension of and reaction to LSD and Eastern mysticism, but instead emerges out of the influences of a psychic space of genuine otherness worming its way into society. In this way it is impossible to see Deathloop as anything other than a Dishonored game, not just because Arkane chose to set it in the same universe and base much of its plot on the aftermath of the killing of the Outsider, but because it treats our own history and world in the same way. It understands History as that which makes the present, and actualises this fact in the way Blackreef itself is layered with strata of previous histories and futures, from the antiques of Dunwall’s imperial might to the futurism of quantum and atomic technologies.

This obsession with historical materialism even seems to suggest some kind of universal teleology, that History has stages that manifest even in other (fictional) dimensions, where modernity is driven by whale oil and the space race was oriented towards an occult void. Deathloop proposes that we can identify the precession of societies as if they are running by clockwork. Dishonored ultimately forms the History of Deathloop, the great myth of power and social change that reinforces the conditions of its contemporary society. That Dishonored also forms Arkane’s own origin story, its own great myth, seems only appropriate then. Yet there is an endpoint here, because as History catches up with the present it begins to see its end, just as when the loop is finally broken in Deathloop we are greeted with dried oceans and burnt skies, namely the end of the world. Where can History take us from here, or to put it more simply, is Deathloop Dishonored’s continuance into the future, or simply its end?

***

Gareth Damian Martin is an award-winning writer, designer and artist. Their first game, In Other Waters was widely praised by critics for its “hypnotic art, otherworldly audio and captivating writing” (Eurogamer). Their games criticism has been published in a wide variety of forms and they are the editor and creator of Heterotopias, an independent zine about games and architecture. Their second game, Citizen Sleeper, is coming in 2022. Find them @jumpovertheage.