The hacker is lost again. He’s wandering aimlessly through the identical LED-lit corridors of a sprawling space station, checking the corners for a missed item or the nondescript chunks of plastic that contain voice memos and emails from now-dead workers. The hacker will shoot robots and mutants in small blasts of muted excitement before returning to studying the grid of a blueprint-style map, once again wondering where he ought to be going in his quest to survive a labyrinthian cyber hell. He hopes to not be lost at some point in the future, trusting that whatever hints might reside within the painfully dull recordings logged in that videogame staple, the all-seeing, all-hearing, menu-based techno-diary will guide him to salvation.

For some players, becoming lost in Citadel Station in this year’s remake of 1994’s System Shock will provide the thrill of a nostalgic return to a well-loved setting. For others, it will offer an academic exercise in checking out a classic shooter, slightly tweaked with hi-def visuals. Importantly, all but the most devoted fans of the original game will spend most of their time with the game hopelessly lost—an unfamiliar experience in the present year, when mainstream games take such pains to ensure that the stretches of confusion and boredom that make up the 2023 System Shock are never given an opportunity to arise.

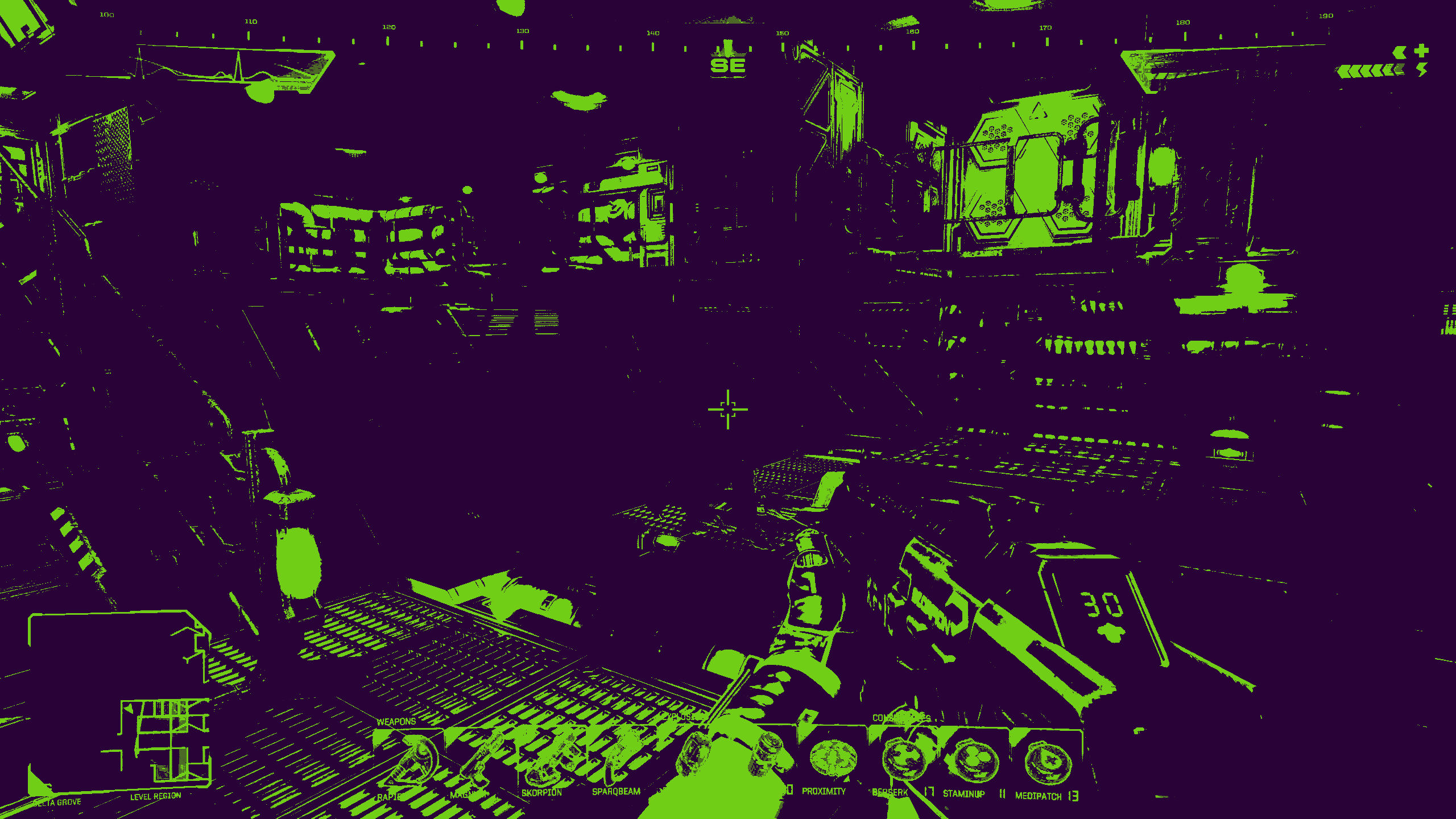

The game, yet another of the splashy, disconcertingly frequent remakes to come out in recent years, is a look back in time that distinguishes itself largely by how faithfully it recreates the original. Aside from its audiovisual update—which, despite wearing thin over the game’s bloated runtime, is a well-realized blend of contemporary and mid-‘90s aesthetics—System Shock is very much the same game as it was in its original, 30-year-old version. Players collect guns and equipment, scooping up items useful in their current form or suitable only to crunch down and sell as recyclable material. They try to escape the deadly, computer-festooned labyrinth of Citadel Station while hunted by synthetic and mutated enemies and are threatened all the while by an evil artificial intelligence called SHODAN. They get lost.

Videogame audiences typically call unfashionable approaches to design “outdated,” though System Shock’s mazelike construction does not belong to a bygone time as much as it does to a fashion, trend, or school of game making. As in DOOM, Marathon, or any number of other first-person games released in its proximity, System Shock assumes that one of the main pleasures of games is exploring and learning the layout of a maze.

Nearly three decades later, now that this approach to design is limited mostly to the niches of dungeon crawling RPGs and the ever-changing layouts of randomized “roguelike” action games, it can feel like a tedious way to inhabit a digital world. Though frustration is inevitable in the process of acclimatizing to System Shock’s style of play, there’s nothing about it that bars contemporary players from seeing the value of its construction. Playing System Shock in 2023 asks us to reconsider our expectations regarding the monolith of easer-to-navigate, easier-to-parse game worlds, not consider current design fashion as a straightforward evolution.

It takes time to find the game’s rhythm, but, once its metre is internalized, it becomes clear that the school of shooter design it belongs to helps more than it hurts its goals. Would System Shock be better if the player didn’t get lost as often? Probably not. The success of the game depends in large part on the sensation of being subject to structures greater than the individual—of slowly learning to navigate a big, pain in the ass space station while figuring out how to overcome its dangers and accrue helpful, life-saving tools along the way. Its form fits its purpose.

The story System Shock tells, though, justifies itself far less. Like some nerdish original sin, its science fiction premise and plot has spawned innumerable impressionable offspring. It also doesn’t exist as much more than an illustrative demonstration in how deeply the roots of videogames’ parasitic tendency to repurpose other works of art and entertainment runs.

The Neuromancer playbook is flopped open, a keyboard-numbed finger underlining Gibson paragraph after Gibson paragraph to crib from. SHODAN is Wintermute; the hacker is Case with all his personality stripped out, ready to be redeployed as dozens of silent shooter protagonists, and the cyberspace he navigates is System Shock’s own. Looking to the movies, Citadel Station is Star Wars and Trek’s ship design put through a blender; the nefarious TriOptimum Corporation is Weyland-Yutani Corporation from Alien and a million other supercorps of its type; executive Edward Diego is Paul Reiser in Aliens and every other smug sci-fi quisling.

If System Shock lifted so liberally from these sci-fi staples for its purposes alone, it would be easier to excuse as an aberration. But the lack of storytelling imagination—or the fact that game creators so frequently return to the same dusty wells for inspiration—means that System Shock, itself derivative, has become a well worn reference text for so much else to follow.

We now have Half-Life and Dead Space and Prey, and a million other easily forgotten examples of games whose plots consist of little more than repairing industrial structures in order to continue repairing industrial structures until credits roll. We have Portal’s GLaDOS echoing SHODAN’s taunts and evil AI in Halo and Horizon. In most of these games, and in so many others, memorable characters and relatable interpersonal dynamics are sacrificed for plot-moving mouthpieces and the story is delivered in post-disaster past-tense: notes to self replacing the joy of back-and-forth dialogue and frozen artifacts replacing the messiness of characters in possession of something like real personalities. As an urtext, System Shock isn’t great.

What’s striking, then, is how prevalent its lacklustre narrative approach still is when compared to how successful and largely absent its seemingly outmoded take on level design appears in 2023. As a medium meant, at least in part, to tell stories beyond the thin incidentals of “stuff that happened to the player,” the mainstream has largely stayed in place, treading water, for decades. In the focus that’s meant to excuse these narrative failures—a concentration on making the act of progressing through a game world enjoyable instead—there’s a similar lack of imagination. Rather than create environments based on the kind of activities or mood the story requires, design genre too often seems to dictate what follows. (An open world game that exists to show off sheer financial power with nothing worth doing in it; an action game with role-playing weapon statistics and branching dialogue that have little to no effect on the action itself.)

System Shock illustrates that big budget games have taken the worst kind of inspiration from the past—surface level aesthetic borrowing without a real appreciation for the actual substance of original works. What we’re left with is more hackers with guns, lost in identikit plotlines, forever and ever, unto the release of yet another sci-fi blockbuster that might as well be named System Shock. There has to be an exit from that maze at some point.

***

Reid McCarter is a writer and a co-editor of Bullet Points Monthly. His work has appeared at The AV Club, GQ, Polygon, Kill Screen, Playboy, The Washington Post, Paste, and VICE. He is also co-editor of SHOOTER and Okay, Hero, co-hosts the Bullet Points podcast, and tweets @reidmccarter.