I’ve tried to separate it into three tiers. Tier one is a kind of total verisimilitude, a Lars Von Trier, Dogme 95, keep the camera rolling and don’t ever interfere level of verisimilitude. Tier two is the Michael Haneke, typical movie experience, lies at 24 frames per second level of verisimilitude—we know that what we’re seeing isn’t real in the true sense, but we can suspend our disbelief and accept it at some level because we apprehend it as a version or an abstraction of the truth. This tier doesn’t show truth, but it uses fiction as a means of arriving at some exaggeration or refraction of truth.

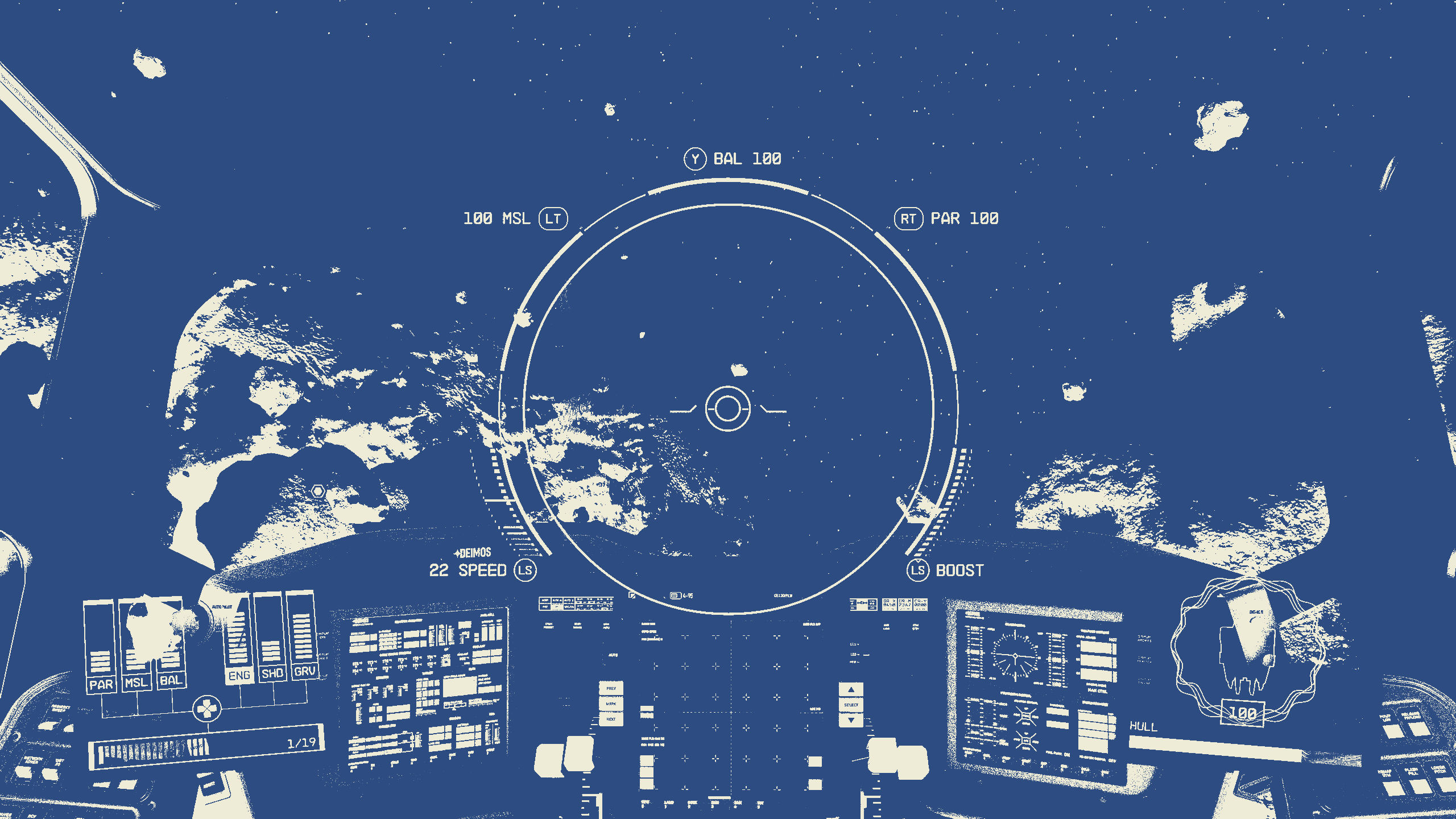

And then there’s the third tier, which is videogames—there’s the exclusively videogame level of versimilitude. At this level, when it comes to truth, you can more or less forget it, because you have to do so much work to suspend your disbelief, and accept so many distortions and abstractions and contraventions of reality, that it quickly becomes clear that what you’re playing isn’t interested in meeting you halfway. It’s not a judgement of quality as such, but when you, the audience or the player, are having to do so much mental, emotional, and psychological work to make the game fit any conceivable version of reality, at some level I think you give up. What you’re playing is so patently untruthful that you begin to feel foolish and beleaguered in expecting or pursuing any sense of truth or verisimilitude in return. I think a lot of this happens owing to what I’d call gameisms, quirks and apparently unresolvable esotericisms of videogame expression that apparently all we can do is dismiss or try to ignore.

Why can I get shot in the head and my character just goes ‘ooh’ and then I eat a packet of instant mash potato and I’m perfectly fine? Well, ‘because videogames.’ Why is it that when Sarah Morgan says we need to go to the transit office in New Atlantis to collect a package, we both sprint there while she simultaneously provides this quite long explanation of Constellation’s history? Because videogames. Why does Sam Coe run up to a little wandering animal, hit it repeatedly in the head with the end of his pistol until it dies, then walk back over to me, look me dead in the eyes and say something like, “you know, me and Cora go everywhere together. She’s even more of an explorer than I am?” Because games.

One of my favourite examples in Starfield was when I first met Andreja, another member of Constellation who can later become a companion. I go into this cave, and she’s there gunning down this mercenary who’s been sent—like me—to recover another of the mythical artefacts+ at the heart of Starfield’s story. She kills the mercenary, and then she follows me through the rest of the cave helping me kill all the other mercenaries, and while she does this, she repeats these short lines of incidental dialogue: “You messed with the wrong woman.” “You’re going to die today.” “It’s over for you.” But then the sort of combat section of the quest ends, and Andreja comes up to you and says something like “I want to talk to you about the circumstances in which you found me,” and starts explaining about how her killing that mercenary and the entrance to the cave isn’t normally like her, and that she feels bad that I’ve seen her in that light. And I feel like I’m playing a game with fucking Edmund Kemper here, who butchered ten college girls then told the cops he knew it was wrong.

But then the thing is, I start to feel like I’m the one who’s kind of going crazy, who’s ranting and raving about something that’s perfectly normal and mundane that everyone just gets and it doesn’t matter. We’re so acclimated and inculcated and fluent in all the videogamisms now that listing and trying to extrapolate on them begins to sound like nitpicking, or a sort of obsessive, quasi conspiracy theory. But at the same time, everyone is always talking about how videogame stories suck and the writing in games is laughable—or if they’re talking about it the other way around, like here’s a videogame with good writing, they’re talking about it like it’s some bizarre, almost inexplicable aberration. And I think this is part of why. It’s not that we should have absolute verisimilitude. It’s not even that we need that second tier, filmic verisimilitude. But so long as games exist on this third rung, where if you think about them for even a second—where if you try to integrate the moment-to-moment activity within a game it becomes completely impossible to experience the game as anything even resembling an abstraction of truth or even fundamental coherence—I think we’re screwed.

For me, this is the stuff we should be working on. It’s not about making games bigger, or making games look better. It’s trying to address this foundational malformation in the videogame form. There needs to be a total reimagination of what games do, and what they make players do, and how games behave in response to both of these. This whole ‘because videogames’ thing is a dead end because if you show that videogame to people who aren’t accustomed with the absurd, contradictory, unaccountable vernacular of games, there’s no chance they’re going to do the psychological contortions necessary to make the game work as any kind of truthful—or even abstractly truthful—whole. I think this is the primary philosophical problem which games have failed or not even attempted to reconcile, that the idiosyncrasies and the expressive techniques and characteristics that are unique to games—the things that make games games, and separate them from any other form—actually serve to undermine their ability to deliver meaning and truth and purpose. As it stands, games, particularly in their AAA and open-world manifestations, feel like a form where the more you attempt to use them, as a form, the further you’re pulled from consonance or the integrity of what you might want to say or express. Forget everything else. Until all this weird, uncanny, discrepant chaos gets solved, even if it’s only at the subconscious level, people aren’t going to take games seriously. Either that, or we’ll have to resort to the other option, which is to say, yeah, games are weird and uncanny and discrepant and chaotic, and that’s what makes games games, and we should lean towards that. Which is fine—I guess that’s an identity. But it feels like a pretty tragic conciliation, and a limit on what games could or would or should be.

///

+ A quick reply to Reid’s article, which covered a lot of the stuff I was originally thinking of writing about Starfield: I think the way that you can recover the artefacts, by literally shooting them out of the rock with a magnum or a shotgun, is the perfect, inadvertent metaphor for the game’s veneration of colonialism. You find something foreign, shoot it a bunch of times, then take it for yourself. The way this is often followed by a pseudo transcendental religious experience—the more you plunder, the closer you get to your allegorical God, that ethereal spirit of discovery—could have been written by John L. O’Sullivan himself.

***

Ed Smith is one of the co-founders of Bullet Points Monthly. His Twitter handle is @esmithwriter.