This article discusses plot details from throughout The Seance of Blake Manor.

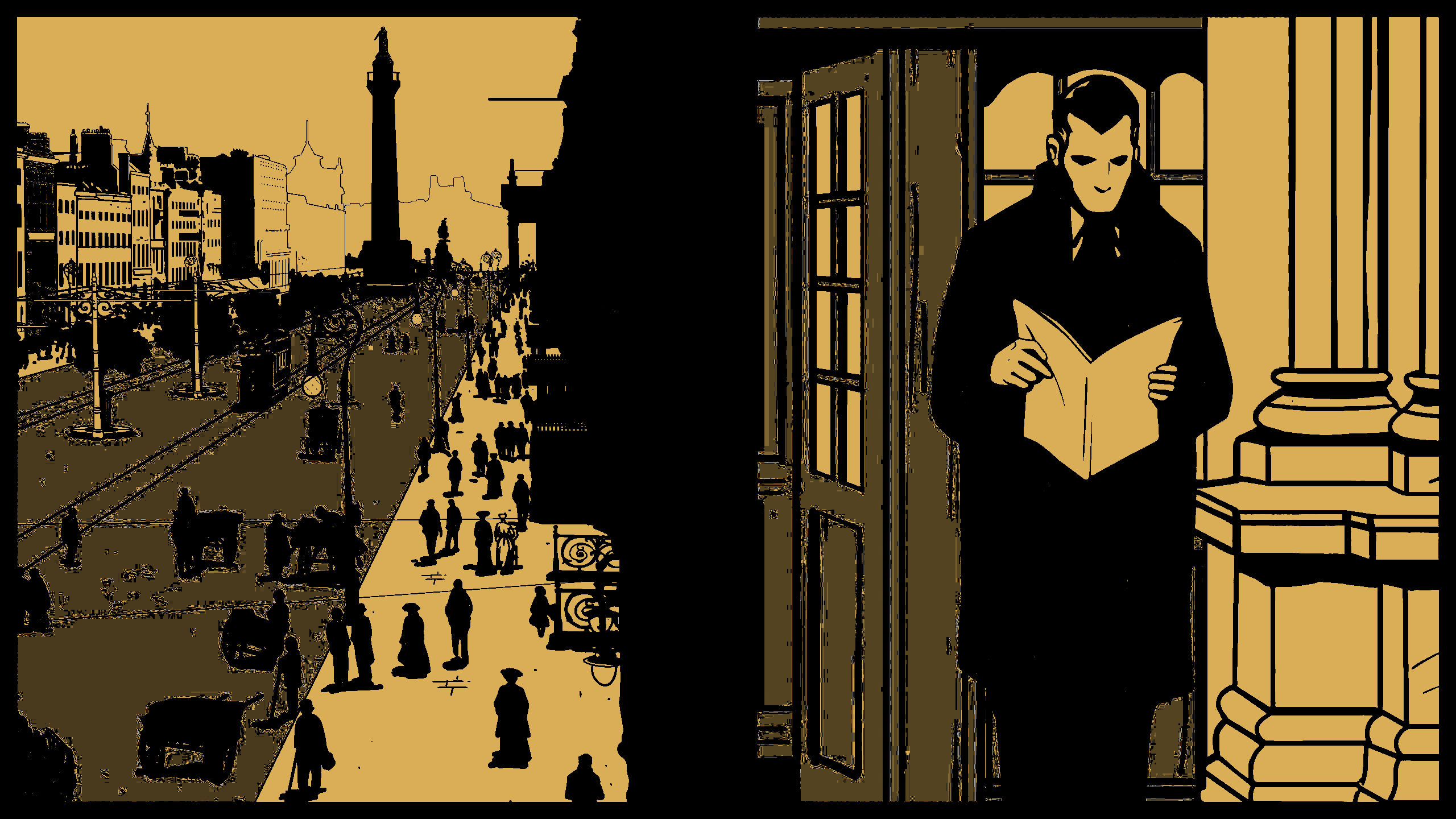

Spooky Doorway's The Seance of Blake Manor is an adventure game with elements of Return of the Obra Dinn, Ace Attorney, and Danganronpa, which is to say it's about digging up dirt on people and confronting them with your findings. You play investigator Declan Ward, come west from Dublin to Connemara to look into the disappearance of Evelyn Deane from Blake Manor+. Deane and many others are gathered at Blake Manor for a grand séance held by the mystic Carmela Mantovani on behalf of Marquess Jonathan Blake.

The game quickly and elegantly introduces you to the entire cast, establishes the stakes, and educates you on its clutch of systems, with none of this feeling like a laborious tutorial or throwaway prelude to the main events. As Ward comes across evidence it's added to his mind-map, where it can be pieced into a hypothesis or raised in conversation with certain characters. Everybody at Blake Manor has a secret. Forming hypotheses about those secrets lets you confront people, dragging their motives into the light and hopefully dissuading them from attending the grand séance, which is obviously bad news.

Cards on the table, I'm generally skeptical of first-person adventure games where the player has freedom of movement through the environment. Point-and-click or grid-based styles always feel like better approximations of space; in a Gone Home-like, or a Blue Prince-like, you spend a lot of time digging uselessly through 3D environments for things to click on. The detail of the space, the weight of it, becomes a series of invisible stretches between hotspots. In a point-and-click game, you move between discrete, composed scenes that present specific information like a photograph. Even pixel-hunting crudely approximates rifling through drawers or stacks of paper. Séance of Blake Manor cheats the shortcomings of 3D adventure games by giving Ward an Arkham Asylum-esque "detective vision" that highlights any clickable object in view. On its face this is ridiculous, of course: this guy can enter a room he's never been in before and instantly highlight the remains of a magic ritual hidden beneath a bed, or a jewelry box on a dresser ten feet away. It's an approximation of investigative acumen—and, to be fair, a "show all hotspots" button is common in point-and-click adventures—but it's also something I barely used. The game's bright, inky colors and sparing set design effectively communicate points of interest, and Ward collates anything relevant into his mind-map.

At this point I'm going to spoil the game's mystery, which is genuinely engaging and genre-literate, so if you want to play this I suggest you do and come back to my truncated summary later. I also want to apologize to Spooky Doorway, who surely in releasing this game did not intend to provoke Americans to speak on Irish history.

Marquess Blake's séance is intended to harvest the magical energy of the guests in order to heal his crippled son Walter, of whom there are many portraits around the manor. The Marquess and staff all say Walter, injured in the accident that killed his mother, lives in the residence, an area of the manor inaccessible until the climax. In fact, Walter is not real; he never was. The portraits are highly skilled forgeries done by ostensible widowed artist Simon Coventry, who is actually Henry Blake, the Marquess's older cousin. Coventry was nearly killed and effectively dispossessed by the Marquess's father when he was young. He fled with his mother and spent his subsequent years learning as much as he could about the manor and its secrets in preparation for reclaiming his birthright.

Mythology and history are so incumbent upon Blake Manor's plot that there is an in-game library Ward has to visit countless times to progress his investigation, researching topics like Irish mythology, gnosticism, and medicine. One of the manor's many secrets is the slumbering immortal Goibniu, locked away in a subterranean chamber. Goibniu is one of the Tuath Dé Danann, generally referred to in Irish myth as the precursor race to the áes sídhe or fair folk, and the race that shares Ireland with the Milesians, or humans. The blood of those killed during Oliver Cromwell's ethnic cleansing of Ireland seeped into the ground and infected Goibniu's dreams. Coventry uses a "shrine of images" to further warp Goibniu's dreams and conjure the reality of Walter Blake in the minds of everyone attending the séance; like those of the caged angel in Thomas Ligotti's "Miss Rinaldi's Angel," Goibniu's dreams become "maggots of the mind and soul." Using Jonathan Blake's blood, Coventry will free Goibniu from his tormented slumber and in return ask to have his youth restored++, thus reclaiming Blake Manor while incarnated as the young Walter Blake, fully legitimate in the eyes of the law and the manor's inhabitants.

The mention of Oliver Cromwell jumped out at me. Per historian Mark Levene, Cromwell's "extirpation of the Irish revolt" of 1641 was "recognisably akin to the ‘dirty’ counter-insurgency wars of the twentieth century" where an imperial power "seeks to win a struggle against an alternative political programme by treating not just the insurgents but their whole supporting population as equally guilty and thereby expendable."

The staunchly Protestant Cromwell also saw his campaign against the Catholic Irish as a divine crusade. Historian A.J.P. Taylor says "God was for Cromwell what the general will was for Robespierre or the proletariat for Lenin: the justification for anything he wished to do."

With this in mind: Blake Manor was given to Edward Blake as spoils of war by Cromwell after the end of Cromwell's genocide in 1652. The Act for the Settlement of Ireland "re-settled" the land won back only a decade prior by the Irish Catholic Confederation, bottling up the native Irish population on a Connacht preservation while 10 million acres of expropriated land were divvied up among underwriters of the war and members of Cromwell's army. However, this newly landed cohort did not account for the whole of Ireland and no mass migration of English Protestant settlers was forthcoming, so the remainder of the expropriated land was owned by English landlords and rented to Irish "tenants," many of whom were renting the same land they had lived on previously.

Coventry's intricate revenge plot—inventing a suitable heir, writing that fictional heir into reality, and then becoming that heir—is what Levene calls the "model perpetrator's 'never again' syndrome" in microcosm. "‘Never again’ would the Irish be allowed to harm righteous Protestants but also ‘never again’ would they be allowed to defy English order." Rights for me and not for thee; the logic of Coventry's revenge can't be extended to the people who predate his claim on the land. His revenge has the veneer of righteousness, but underneath it's nothing but score-settling. The "dream" of birthright is inherently poisoned; it rests on a selective and self-serving narrative.

By rooting out petty grievances and musty grudges and convincing his fellow guests not to attend the séance, Ward effectively marshals facts and logic into battle against self-delusion. The conventions of the adventure game serve him well here. But Coventry can't simply be dissuaded from his revenge; the detective mechanics are useless against him because the facts of his past, his buried trauma, are a fiction. Ward instead has to fill in the blanks around the real Coventry-Blake, winding closer to the truth of his identity and his motive by groping in the dark. Beneath Blake Manor, the tainted dreams of Goibniu radiate, soaking the manor in a false reality where the land belongs to whoever's name is on the deed and the path of history is true and just.

+++

+This is one of those games where the artstyle is "inspired by" an artist, in this case Mike Mignola, and we all understand "inspired by" to mean "it looks exactly like" Mike Mignola!"

++In doing so, Coventry is weaponizing "Irishness" itself, warping folklore and history into a propaganda narrative. Irish-Americans should be familiar with the notion.

***

Astrid Anne Rose is a long-time contributor to Bullet Points. Her work can be found in MEGADAMAGE, BOMB Magazine, and The New Lesbian Pulp, as well as on Gumroad and itch.io.